TCR Talks with Hazel Kight Witham, author of The Truth about Secrets

By Jesenia Chavez

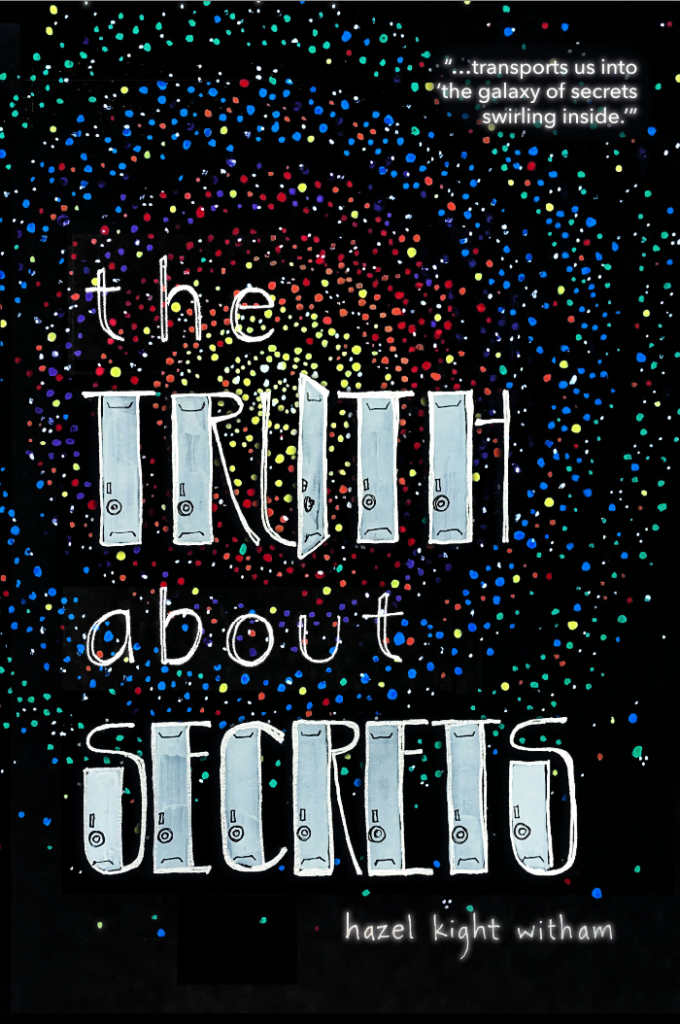

In her debut book, Hazel Kight Witham delves into middle school with a memoir in verse. She zeroes in on a fateful day where a young Witham reckons with her own fear and shame at her classmates discovering she has two moms. She loves her moms, Judie and Sharon, but middle school is an unfriendly place for anyone whose family does not fit into a heteronormative paradigm. Middle school, with all the awkwardness and intensity of pre-adolescence, comes to life on the pages through beautifully crafted poems with vivid details. Through notes interspersed throughout the book, Witham seamlessly weaves details of queer history that serve as a balm for her younger self and help to educate those not familiar with the activists and leaders of LGTBQ+ communities. This is a genre-defying narrative that reminds us of the power of community, and through sharing her experiences, Witham honors both the brave people in her life and the ones throughout history who continue to fight for fairness and justice.

THE COACHELLA REVIEW: When did the seed get planted for the story?

HAZEL KIGHT WITHAM: I first found the power of telling the story when I was in high school. The story itself is about the power of telling stories—telling our truth—and the first time I really wrote about that day that was so transformational was when I was writing my college essay. I’d decided to write about that day. That was still at a time when there was so much closeting and silence, and I feel like that essay helped me get into college. That was where I first really zoomed in on that day.

For this book, I started doing National Novel Writing Month with students back in 2008. My writing partner Noriko Nakada and I tried it out one summer. She introduced me to this crazy idea of writing a certain amount of words every day for thirty days and seeing what happened. I wrote a story, and then we started trying it with students, and it quickly became one the best months of the year doing this absolutely inconceivable thing with young people. I was teaching middle school, and Noriko and I both would write with our students.

Then in 2012, I started writing the fiction version of this story where I was trying to set it around the same premise. I was like, Why am I writing it as fiction? I also tried writing it in prose and thought, Let me try just telling the story, and I decided to try it in verse because I had seen there were only a handful of [single-subject longform] books at the time that were in verse, and I loved how they allowed young readers to move through a book a little more quickly. I felt like the story needed the space that a book in verse would give it, so 2012 was when it was really born, and then it evolved from there.

TCR: A lot of times, it’s hard to stay with one particular story, but you stayed with this idea and tried it in different genres. What kept you coming back?

HKW: It’s such a good question, because I think as much as we want to finish a thing, sometimes putting something aside and then coming back to it with fresh eyes is essential. I think the fact that it was in verse made it a more accessible book to continue working with. I did get an agent in 2014, and she and I started working on it, and she was giving me notes. Having somebody give feedback was really helpful, and we did a lot of revision with it and then she started shopping it, and it got some lovely passes. You know, some lovely, Ooh, love the writing, or, Love this, but we don’t know how to sell a book in verse. But I knew that students would read [it]. Ultimately, nobody picked it up and my agent went off to become a social worker, so she left the literary world. I thought, That’s wonderful for her and all the people she’s going to help, but now I’m solo.

Over the years, I would send to agents, and I also kept going back to [the manuscript] to add new layers because I thought about how, as a teacher, I wanted to have something in there about what I wish I had known as a kid. What I was lacking at the time was all about representation; it was all about knowing our queer history and how influential queer folks have been in so many spaces of change. I decided to start adding those little notes about things I wish I’d known, so it evolved quite a bit from when it first was heading out into the world, and then one pivotal thing that helped me keep going was I read it out loud to my partner, my husband, and he’s a brilliant writer, editor, and comedian. Just reading it out loud gave it new life for me and made it real in a way that it hadn’t [been before]. He’s a tough critic, so it was great to have that. That sort of drove me to be like, Okay, I gotta make this happen.

TCR: It’s such a unique thing you did with the notes you added, giving people those resources as the story moves along, and it didn’t take me out of the narrative. It reminded me of how we engage with social media. We already Google things or click on hyperlinks for more information when we are reading an article or an e-book. I haven’t seen anybody else do that. When you were adding the notes, how did you find that balance?

HKW: The notes came later. That was one of the last passes and I did that during a writing residency. My writing partner and I would do these writing retreats, because we’re both parents and teachers, to give ourselves a week at some place to have some ability to really focus. I used a couple of those residencies to research and learn more myself and read books about the queer rights movement, and then I just started thinking about different moments, what I wished little Hazel had known and things that just stuck out to me. I was super obsessed with Frida Kahlo when I was in high school, and then to learn about her and think about her as this queer icon, I was like, Oh my God, I have to put Frida in here somewhere. Also people like Bayard Rustin. I had no idea how influential he was until a friend told me more about him. I just felt like it was an opportunity to add things in, because the narrative is so tightly focused on that one day, I wanted little sips of the larger historical context.

TCR: You also capture the feelings of being in middle school and [adolescent] friendships so well. The tension builds, and everything feels so important and intense at that age. How did you get to that place of remembering your middle-school self?

HKW: It certainly helped that I was teaching middle school at the time. And as an English language arts teacher, you tell stories to get students to think of their own stories, so I had told some of these stories to my students, like the one about punching a teacher. It was really great to be immersed in middle school when I was trying to tell a middle-school story. Those friendships—I changed all their names, but those are still my friends. We have been friends since middle school, and I think the friendships that were forged in middle school, if you hold on to those…they’ve seen you at your most vulnerable and awkward, and to have people that know this history about you is vital. I’m still very connected to those women. I was just talking to the character that’s [called Iris in the book] on the phone. They’re my sisters. I think they helped me remember, too. That day was so pivotal that it is really burned in my memory, [and] writing is an act of remembering.

TCR: Okay, so let’s talk about your wonderful moms. You are honoring them and their stories [with this book].

HKW: That was another significant driver of getting this book out. Sharon passed away in 2015 after battling a really belligerent cancer, but she did get to read one of the early drafts of this book. And to see my mom get to watch the book come to life—she’s been my biggest fan and my West Coast publicity. She’s just been incredible for a girl who grew up in small-town Texas where she didn’t even know gay existed. I mean, in the ’40s and ’50s it wasn’t even a thing in her awareness, so it’s been really cool to have this book celebrate them. They were such great parents [and] phenomenal models of what a strong, equal relationship looks like. There was none of the oppressive patriarchy in my home. I grew up in a matriarchy, and it was incredible to watch that.

TCR: Now that your mom has read it, what does she think?

HKW: She just loves it. It’s so cute, because I have a group of aunties—all these gay women that always used to come over for Thanksgiving—and they’re just part of our family. I mean, that’s one of the beautiful things about the queer community, how you can create your own family—intentional families and chosen families. My mom was having a hard time one day—she battles with a lot of anxiety—and her friend, who’s obviously read the book, told her to go reread page 52 and think about what Sharon would say. It’s been wonderful for my mom to have the amazing things about Sharon celebrated in the book. She was at my book launch in June, and I could see her in the back row crying and watching me read. It’s been very special and I think [her reaction] was one of the things too, that [made me think], I can’t wait for the gatekeepers… to tell me that this book is ready to go out in the world. I have to just take charge of it and put it out. I’m done with people telling me no.

TCR: You’ve mentioned Noriko Nakada as your writing partner. How has this relationship helped your writing? She is also your publisher, right?

HKW: Noriko and I met in 2005 through teaching circles, and we were both on this grant that would send us on the weekends to work on curriculum. She was in her MFA program at Antioch, and I got to hear about that program that’s a low residency program, too. I thought, I want to do this, and when I was still in the program and she had finished it, we started talking about how we would make time and prioritize our writing lives. So one New Year’s Eve, we decided, Let’s meet in the morning before school starts at 6:00 AM in a coffee shop. Let’s be writers before being teachers.

Noriko had created Strikethrough Press for her memoirs, and she had been telling me for years that they were accepting submissions to publish. Finally, I said yes. Now, we swap pages, and we are finally working on a project together—a collaborative project. It’s a teaching craft book to help teachers return to some old-school practices to improve connection in the classroom after all of our screaming during the pandemic. That’s our first real collaborative one, but we’re more about accountability. Now we don’t meet at a cafe anymore, but every morning of the school year we text each other and check in. We know that’s us sitting down to the page.

TCR: You are an award-winning teacher and writer. What’s next for you?

HKW: I’m going to continue to help this book have life out there. I had no idea what it would be like to have readers, and the response has been incredible. There are texts that I’ve gotten from friends or from people who took time with it, like my mother-in-law. I got to share it with her this summer, and she read it immediately and got choked up about the good that this book will do and how many people she feels like it will help.

Jesenia Chavez is a proud Chicana, 18-year veteran public school teacher, storyteller and writer. Her poetry collection, This Poem Might Save You (me) is a journey through the streets of Los Angeles that explores intersectionality and the rituals of survival. She has an MFA from UCR, where she served as poetry editor of The Coachella Review. Find her at https://www.jeseniachavez.com IG @chabemucho

Jesenia Chavez is a proud Chicana, 18-year veteran public school teacher, storyteller and writer. Her poetry collection, This Poem Might Save You (me) is a journey through the streets of Los Angeles that explores intersectionality and the rituals of survival. She has an MFA from UCR, where she served as poetry editor of The Coachella Review. Find her at https://www.jeseniachavez.com IG @chabemucho