Book Review: Optic Nerve

By Jackie DesForges

Several years ago I visited the Picasso Museum in Malaga, Spain. At the time, each gallery was arranged by theme rather than chronology, so that as you made your way through, you weren’t seeing Picasso’s works in the order they were —created—you would see a ceramic he created in the 1930s next to a drawing created at the end of his life next to a painting he made in the 1920s, all seemingly random until you realized that they focused on the same theme or subject. María Gainza’s debut novel Optic Nerve reminded me of this museum from the very first page. The story doesn’t proceed chronologically through the narrator’s life, but rather thematically. Beginning each chapter feels like stepping into a new gallery, perhaps especially because the book deals directly with the history of visual art.

Several years ago I visited the Picasso Museum in Malaga, Spain. At the time, each gallery was arranged by theme rather than chronology, so that as you made your way through, you weren’t seeing Picasso’s works in the order they were —created—you would see a ceramic he created in the 1930s next to a drawing created at the end of his life next to a painting he made in the 1920s, all seemingly random until you realized that they focused on the same theme or subject. María Gainza’s debut novel Optic Nerve reminded me of this museum from the very first page. The story doesn’t proceed chronologically through the narrator’s life, but rather thematically. Beginning each chapter feels like stepping into a new gallery, perhaps especially because the book deals directly with the history of visual art.

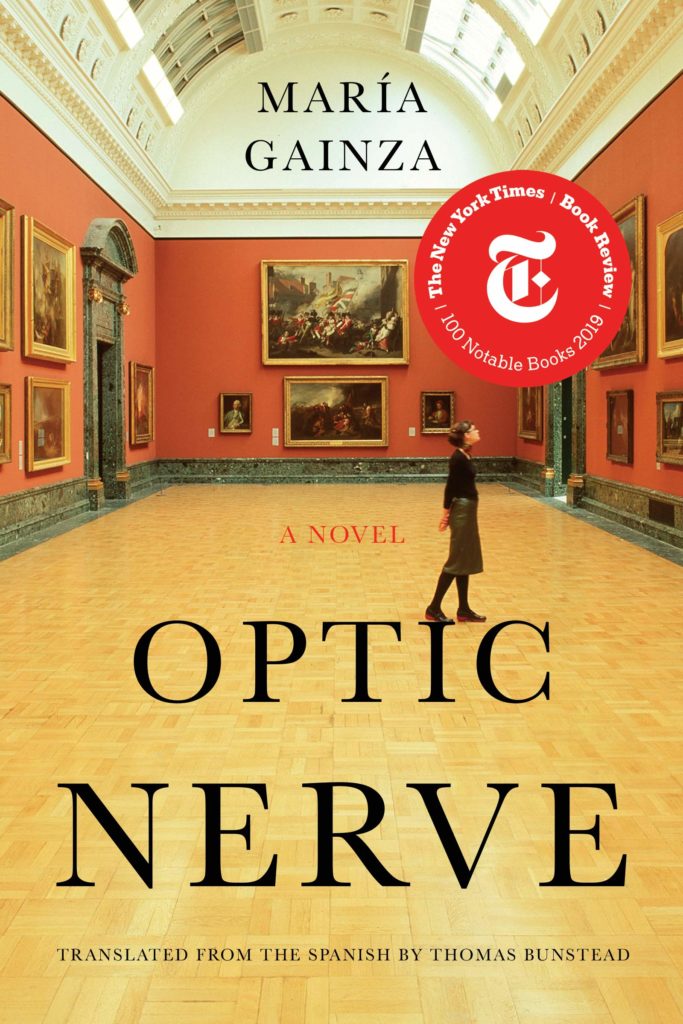

Like her narrator, Gainza is an Argentine art writer and tour guide named Maria. This is her first novel and first piece of writing to be translated into English, and The New York Times has already placed her in the league of other notable authors of auto-fiction like Rachel Cusk and Ben Lerner. I’d personally add Maggie Nelson to that list, as this book reminded me of Nelson’s Bluets; each writer meditates on the way you can trace your life through the lens of the thing that obsesses and possesses you: in Nelson’s case, the color blue; in Gainza’s, visual art.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#cc0000″ class=”” size=””]Gainza’s experience as an art writer allows her to give art historical context and biographical artist information without being heavy-handed about it. Her language is approachable and unpretentious, but still authoritative. She describes artworks in such vivid detail that you won’t need to Google them in order to imagine what she’s talking about (although it’s fun to look them up after each chapter just for kicks) . . . .[/perfectpullquote]

Though the book is a work of fiction, all artists and artwork featured in the story are real. Some, like Gustave Courbet and Mark Rothko, are familiar even to those who haven’t spent much time in the art world. Others, like Hubert Robert and Miguel Carlos Victoria, are lesser known even to those of us who have studied art history. What each of the works has in common is an emotional resonance with the narrator, something that links each artwork to a particularly critical point in her life. In an early chapter about her pregnancy, she describes the work of artist Cándido López, who lost an arm during his time as a soldier. Immediately, I was hooked. Any writer who compares the morphing of the human body during pregnancy to the violent loss of a body part during war has my attention and my morbid respect. The shock one feels in both scenarios, the loss of control, learning to navigate life again with a body that may not be capable of what it was before.

Gainza’s experience as an art writer allows her to give art historical context and biographical artist information without being heavy-handed about it. Her language is approachable and unpretentious, but still authoritative. She describes artworks in such vivid detail that you won’t need to Google them in order to imagine what she’s talking about (although it’s fun to look them up after each chapter just for kicks): “It came to Rothko in the summer of 1945, while he was in the process of setting down on canvas a series of abstract, blurry blocks of color floating in space. All notion of line and detail had disappeared, and color itself exploded: pinks, peaches, lavenders, whites, yellows, and saffron, as evanescent as steam on glass.”

Each chapter generally follows two storylines: one of an artist, and one of the narrator’s. The chapter about Courbet’s The Stormy Sea reads like a beautiful, quiet eulogy to a cousin whom Maria both loved and couldn’t understand. This cousin, also named Maria, created floor-to-ceiling green and blue collages that looked like “seeing one of Courbet’s waves from the inside.” A chapter dedicated to Maria’s childhood friend Alexia is paired with a self-portrait by the Japanese artist Foujita. Both Alexia and Foujita moved to new countries in an effort to establish new identities outside the context of their childhoods and their “born roles”—Alexia from Buenos Aires to Spain and Angola, Foujita from Tokyo to Paris and London. It’s a reflection on the balance between finding your identity and losing or rejecting parts of your past that actually make you who you are. The chapter about Mark Rothko’s color-block paintings describes the way the brain processes color both technically and emotionally, and it also follows Maria to an eye doctor after she experiences tremors and blurry vision, worried that she might be going blind.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#cc0000″ class=”” size=””]This book is about a life of following rules, certainly, but it’s also about art, the reasons we make art and look at art, the things we say about it, and the things we think it says about us.[/perfectpullquote]

The book shifts from first person to second person in two chapters; the first switch comes after Maria has given birth to her daughter and literally has a “second person” in tow; the second switch comes towards the end of the story when Maria describes a newly-formed phobia around air travel. In both cases, the switches come at periods in Maria’s life when she doesn’t feel like herself, when she feels like she has stepped away from who she has always been: “It was the most wayward thing you’ve done, in a life of following rules: standing up a dozen illustrious curators in Geneva.”

This book is about a life of following rules, certainly, but it’s also about art, the reasons we make art and look at art, the things we say about it, and the things we think it says about us. Look closely, Gainza tell us. Look at your life like you’d look at a favorite painting, and see what happens.

Jackie DesForges is based in Los Angeles and is pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing through the Low Residency program at UC Riverside. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Exposition Review, Matador Network, and more. She is currently working on her first novel and you can find her on Twitter and Instagram at @jackie__writes.