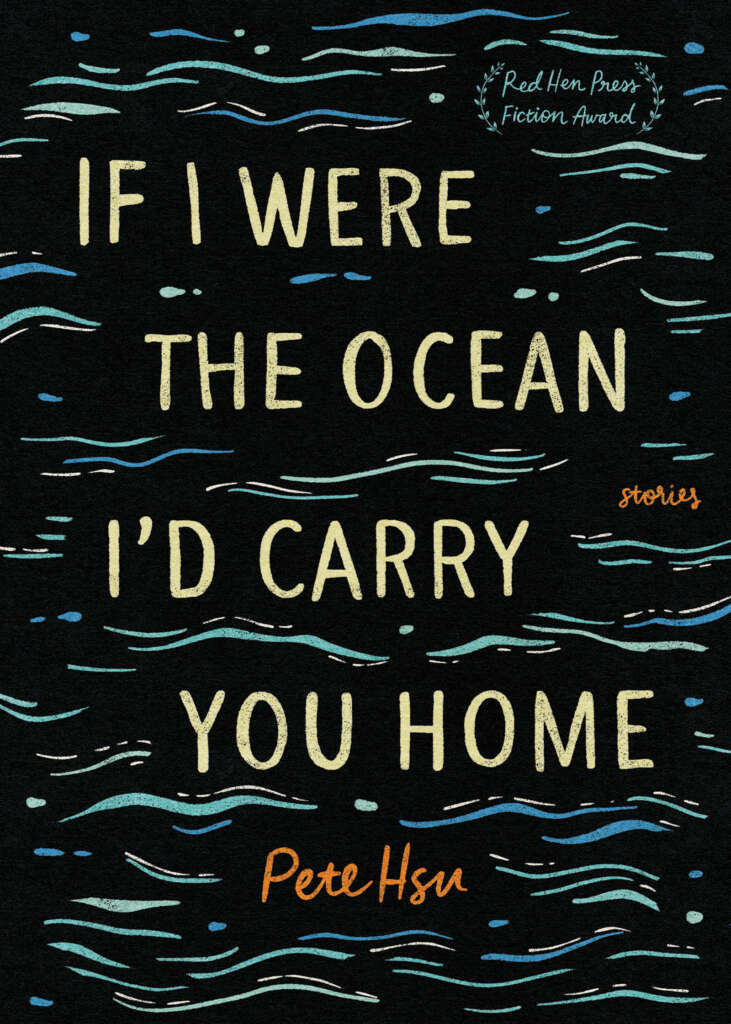

TCR Talks with Pete Hsu, Author of If I Were the Ocean, I’d Carry You Home

Interviewed by Luree Scott

In Pete Hsu’s short story collection If I Were the Ocean, I’d Carry You Home, the struggles and sorrows of childhood are brought to light with a fully compassionate view. Family, friends, and strangers change the trajectory of one another’s lives in small ways that are rarely noticed, but Hsu has a way of enlarging moments of intense emotional conflict to show how sometimes it really is the little things that develop so largely in our hearts. While the first six stories are more focused on the perspective of children and how their emotions develop as a result of their upbringing, the second half of the collection focuses on the repercussions of these upbringings as the protagonists journey through adulthood. Some characters even reappear to reveal how these small moments culminate into the fullness of their lives.

The young age of many of the protagonists doesn’t spare them from the horrors of life. There are incredibly insightful investigations of immigration, toxic masculinity, the AIDS crisis, grief and loss, infidelity, and abandonment threaded throughout. And yet, through the darkness, the soul of each character is delicately laid out on the page. The characters make mistakes. They become trapped or set themselves free. They try their best to understand the world and themselves in the process. Hsu takes the universal truths of human experience and weaves entirely new tales of beautiful confusion. Perfect imperfection.

We asked Hsu more about these characters and the writing process, uncovering a few surprise influences, from Dungeons & Dragons to the mythology of Westerns.

The Coachella Review: Since this is your first full short story collection, I’m curious about your journey as a writer. How long have you been writing? Was there a specific reason why you wanted to pursue storytelling?

Pete Hsu: I’ve been writing since I was a kid, but as far as publishing, I had my first story published in 2016, “A Penny Short.” It was a scene from a novel manuscript that didn’t make it past the first draft. Since then, I’ve had a lot of luck and help along the way. I was a 2017 PEN America Emerging Voices fellow, which at the time was a Los Angeles-based fellowship that really gave me a huge leg up in my writing, in terms of both the craft and the business/community.

I don’t know if there’s a specific reason why I wanted to pursue storytelling. I just always liked it. When I was a kid, I was Dungeon Master in my D&D group. As a teenager, I wrote little Stephen King knockoff stories to share with my friends. It’s just always been fun for me and also something I gravitated towards. Another thing is I have a terrible memory. I just cannot remember things: personal history, facts, definitions, details. Much of this eludes me. So I would make stuff up if I didn’t know. Which is something I still do today.

TCR: D&D is such a great way to understand character development and storyline. Were there any campaigns you ran or characters you made that you were proud of? I ask as a fellow D&D player who loves the chance to chat about it.

PH: It was so long ago! I can’t recall any specific campaigns, but I still have a fondness for how chance played into everything in D&D, from generating character traits to the outcomes of conflicts. I think about that a lot, as a writer and reader, that there is a randomness to everything, that whatever you do, it’s a roll of the dice.

TCR: The structure of this collection was extremely clever. What did the process of picking and arranging these stories look like? Was the structure always in mind or did it come about more organically as the collection was created?

PH: In putting the book together, I looked at some great collections to see how they did it: Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, Jennifer Egan’s [A] Visit from the Goon Squad, Siel Ju’s Cake Time, and, maybe my favorite book of short stories, Ottessa Moshfegh’s Homesick for Another World. I looked at how the stories were picked, arranged, the connective tissue in between stories, the larger narrative arc of the book as a whole. It took a lot of trial and error, but in the end, I made a decision to order the stories based on how the protagonists age. So the youngest protagonist is Paul in the first story, “Pluto,” and the oldest is Reggie in the last story, “There Are No More Secrets on Planet Earth.”

I began the book with a mental image of a spiral staircase, going over the same ground over and over again but also moving up and down as you go. So each pass is the same but also different. There’s repetition, but also progress, or regress. That’s demonstrated in “Pluto,” a story about a father and son running laps around a high school track.

I wanted If I Were the Ocean, I’d Carry You Home to end with an image of looking back in time, and “There Are No More Secrets on Planet Earth” is literally about a TV that shows us recordings of our past.

TCR: The writer side of me is very interested in the process of reprinting previously published stories into a new collection. For those stories that you had already published, were there any big changes that happened with them in the editing stage of If I Were the Ocean? Did parts of the plots change, or were they virtually untouched? And how did you decide which stories to revisit?

PH: I did some revision of the previously published stories. Not so much with the characters and plot, but in terms of technical stuff, like point of view and whether it’s present tense or past tense. This was to maintain narrative flow and also to avoid confusion. I think one issue that came up for me was that two different but consecutive first-person narratives could read like they’re the same protagonist.

For the “Reggie” stories, which are a through-line in the book, I wanted to make sure the timeline was solid. I wanted the other characters to be consistent in terms of age, relationships, names, and so on. This wasn’t a problem with stand-alone stories, but when they’re all in one book, it becomes important to keep that stuff organized.

TCR: What made you choose Reggie as a character to return to and explore with multiple stories?

PH: It may say more about me than I want it to, but Reggie is a stand-in for me, my fears and anxieties, my regrets and failures, hopes and longings; that’s what Reggie embodies. And also, that Reggie is a survivor. Bad things happen to him. He also makes a lot of bad decisions of his own, but somehow he forges deep and meaningful connections with people along the way. He finds a way to be close to the people he loves. He is so flawed, yet he has a meaningful life. I hope that I can end up the same way, and I do believe that I can—that everyone can.

TCR: I noticed that many of your stories covered dark or sensitive topics, such as domestic abuse and gun violence in “From the Brush, a Frantic Rustling”—which has an ending that still haunts me today—or the AIDS crisis in “Game Five.” What pulls you towards these kinds of issues in your writing?

PH: I don’t go into my writing with a political agenda, meaning I’m not writing to try to argue a political position with my reader. Though I’m sure some readers would disagree! This might be because, in the end, all writing has a political component. It’s unavoidable. The things we include and the things we avoid, they all say something about how we see our larger society, where factions vie for power, and this inevitably impacts how we imagine our fictional universes.

So my characters are impacted by racism, class, religion, misogyny, homophobia, and so on. These things will affect their stories, and so whenever it’s appropriate, I present them.

TCR: You also view these issues from a wide range of age perspectives. What is it like to write through the eyes of a younger or older person?

PH: There’s a kind of random reason why I write so many seven-to-nine-year-old characters. My wife has been a second-grade teacher for a long time, and so in my mind, all kids are eight years old. There’s a bunch of characters in this age range in the collection. Paul in “Pluto,” Reggie in “King Kong Korab,” Penny in “From the Brush,” Scharlene in the title story.

For the book as a whole, the age range is probably a product of my thinking about how people’s lives are affected by generational events. I have a background in family therapy, and one of the core ideas I was taught was that every individual is a part of multiple systems, and when something in a system changes, the individuals within that system are affected. So for example, if a father dies, then the story for the child left behind will be different from the story if the father had not died.

TCR: I love that your wife’s experience with teaching gave you a certain perspective of children that echoes in your writing. Who else in your family system do you think has influenced your stories?

PH: I think about a lot of my family when I write; consciously or not, they’re in my head. My birth father died when I was a toddler, so that core sense of loss is often in my work. And my dad, the man who raised me, I often think about in terms of how people find themselves in complicated situations and sometimes rise to the occasion, and sometimes not.

TCR: I also noticed that sports are often outlets for your protagonists to process their complex situations. Like, in “Game Five,” I loved how you used the five games of the 1991 NBA Finals to frame the story. I also really appreciated how, in “Pluto,” the laps on the track became aligned with the stages of never-ending grief. How do you think sports affect the way you tell your stories? How do you think they affect the way we relate to each other?

PH: I’ve always liked watching sporting contests. I love the drama, the competition, the physicality. I love the sacredness of it, too, how there are all these arbitrary rules about space and behavior and meaning that all the players and spectators have to abide by. It’s religious almost. I’ve actually heard that stated. For example, that NFL football is the new temple.

I’ve also grown to think of sporting events as narratives. In each case, there is a protagonist who is trying to achieve a goal, and an antagonist that is in the way. They’re a lot like stories. Everything must happen within the space between the beginning and the end.

TCR: Is there a particular sport that has become sacred to you?

PH: I’ve been a Raiders fan since 1984, when they moved to L.A. and won the Super Bowl. So for a long time there was some ritual to it, especially the clothing. I became obsessed with getting exactly the right Raider jersey. The lettering and numbering had to be exactly right in shape, material, position, and the cut of the shirt, the labeling, everything. There was a religious quality to that, a deep and reverent abidance to some invisible perfection.

TCR: Speaking of sacred things, religion is also a big factor in stories like “Korean Jesus,” “If I Were the Ocean, I’d Carry You Home,” and “There Are No More Secrets on Planet Earth.” It’s incredibly refreshing how you take some notable stories from the Bible and turn them on their heads, making what is generally seen as concrete and unchangeable into something completely unexpected and unique. What led you to these new twists and perspectives?

PH: For a while, in my twenties, I was a part of the Evangelical Church. It was the ’90s. I think this was when Christianity in America really went all in on a right-wing agenda, a fundamentalist theology and an unrepentant conservative political ideology. That was really heartbreaking for me. I was, for quite a while, a true believer in Jesus, especially the anti-capitalist/anti-money Jesus that I saw in the Bible. But all around me, Christianity started to be about being pro-guns, pro-business, anti-LGBT rights, anti-abortion, anti-feminism, anti-science. All this had nothing to do with why I was drawn to the religion.

It didn’t take much to see that the fundamentalist position was absurd. So I stopped believing in the literal idea of the biblical God. But I found it really interesting that the God of the Bible could be so easily co-opted by an agenda. There is so much room in the religion to tell the stories in a way that fits any agenda. I kinda hate that, because of the terrible things people do in the name of religion. But I love it, too, as a reservoir for stories. If we can have an AR-15-wielding Rambo-Jesus, then why can’t we have an orgy-hosting free-love Jesus, too?

TCR: In “The Donkey Is Definitely Asian,” one of your characters explains the title of the short story by saying, “You know, Asians always suffer in silence.” It’s such a powerful statement. I wanted to know a little more about what it means to you. Is this something you’ve experienced in your life and your writing?

PH: I think this line is complicated in that it reflects a stereotype of an East Asian cultural attitude. I imagine there are many marginalized groups that have been labeled this way. This was the propaganda about enslaved African Americans during the Antebellum Era. This is a narrative we see put upon undocumented immigrants, as shadow people, easily abused because of their fear of being identified.

Regarding Asian Americans, this is especially poignant in our current cultural/political environment. There’s been a big push for Asian representation in Hollywood. There’s been a political awakening in the Stop Asian Hate movement. This is progress. But there’s still a lot of work to be done, especially intersectionally. Asian American artists and activists are increasingly working with other marginalized groups, though still not enough in my opinion.

TCR: I agree there’s more work to be done. Yourself included, who are some Asian American artists and activists you would say are making a difference currently?

PH: In the literary world, there’s been growing Asian American representation with big hits like Crazy Rich Asians, Pachinko, and Crying in H Mart. I also see a lot of great L.A. authors putting out awesome work that’s both artistically and politically powerful. For example, Steph Cha’s Your House Will Pay is a page-turning crime drama but also a close look at how the Black and Asian American communities in L.A. have intersected. Then there’s Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown, which is a total mind-bending/genre-bending romp and also a treatise on how Asians in America have been positioned by the mainstream culture. As far as organizations go, I love what Asian American Writers Workshop in New York is doing, especially with its growing translation department. And Kaya Press here in L.A. keeps putting out beautiful work year in and year out.

TCR: In “Korean Jesus,” you have elements of magical realism, and “There Are No More Secrets on Planet Earth” is very science fiction in nature, but all your other stories felt purely literary. What led you to such a sharp departure in these two stories?

PH: Since I was a kid and up until today, I’ve always loved genre fiction. For books, it was Stephen King. For movies, it was first Star Wars and then horror movies. For TV, I was obsessed with The Twilight Zone—I sometimes think my foundational worldview is built upon Rod Serling and The Twilight Zone. And my next book is a Western.

In If I Were the Ocean, I’d Carry You Home, most of the stories could be categorized as family drama, but there are genre-adjacent stories. I feel like “Astronauts” is a noir story. And “From the Brush” is an adventure story. Of course, “There Are No More Secrets” is science fiction, and “Korean Jesus” has that fantasy/magical realism stuff going on. To me, it’s about having fun with the writing. Creating stuff that lights up my imagination. And also, I think in a cerebral sense, it’s about generating new mythologies. Pushing up against the idea that there is a true “reality.” The Western I’m writing comes out of this idea. There is a reason why the Western genre is separate from the genre of historical fiction. So much of the Western is myth building, creating a story of America and American values. And as America and its values evolve, I think the Western is a great genre to investigate this and recast old storylines.

TCR: I’m so excited that your next book is a Western! My father is an avid Western watcher. Bonanza or Gunsmoke was often on our TV when I was growing up. Hits close to home. I also think it’s very apt that you say Westerns are a type of myth creation. What else can you tell us about your next book? I’m already looking forward to it.

PH: I love that you grew up watching those shows with your dad! From my youth, I’ve had the images from the Spaghetti Westerns embedded in my psyche. I so badly wanted a poncho and a mule like Clint Eastwood in the Dollars movies! Also, growing up in California, we see that the landscape is mostly not the tropical beach paradise that’s often portrayed. It’s mostly the dusty desert of the Western genre. As such, the desert has been, for most of my life, the setting of my imagination.

As for my next book, I don’t want to say too much because it’s still at that awkward, middle school stage where it’s got mood swings and identity crises galore. But I can say it’s a Chinese American Union soldier out for revenge. Thematically, it tries to take on the classic Western themes of vengeance, honor, machismo, marginalization, and individualism, and it presses on those old ideas, challenging them, forcing them to defend their validity.

TCR: You’ve also mentioned Stephen King as an inspiration throughout the interview. Do you see yourself possibly writing horror in the future as well?

PH: You won’t believe it, but I have an Asian American horror Western novel on the backburner! Something like The Gunslinger meets Pet Sematary.

TCR: That’s so exciting! I’ll definitely be on the lookout for those in the future. Now, before we close, I have to ask: Do you have a favorite story in this collection? Which one was the most difficult to write? Which one brought you the most joy?

PH: I do have a favorite, and I have no regrets about it. It’s “The Fatted Calf,” which is the last story that I wrote for the book. I wrote that story as a sort of love letter to America. America is so fucked up! But I still love America. I’m still a patriot. I care very deeply about rural America, conservative America, religious America. Though, I will vote against a lot of their values at the ballot box, and I don’t feel like I could live in a deeply conservative neighborhood, but I don’t want them to be annihilated. I don’t want to live in a country where there are no conservative people, no religious people.

“The Fatted Calf” represents that dilemma—of loving someone but being unable to live closely with them. There’s no easy answer to this. In the story, Princeton and Big Jay truly love each other. They’ve been through a lot together. They both want to do right by their relationship, their shared history. And, I think, they both long for a world where they really could stay close, where they could have a big block party with all the old neighbors. That world seems out of reach, but the desire for that world lives on.

Luree Scott (she/her) is a writer and performer from San Diego, CA. She received a BA in Theatre Arts and English from the University of San Diego and is currently an MFA candidate in UCR Palm Desert’s Low Residency Program for Creative Writing, where she studies fiction and playwriting. She was also the Drama Editor for The Coachella Review’s Summer 2022 issue. Her previous works can be read in The Alcalá Review, Kelp Journal, Little Thoughts Press, GXRL, Grande Dame Literary Journal, and Longleaf Review. Her Twitter is @luree_s.

Luree Scott (she/her) is a writer and performer from San Diego, CA. She received a BA in Theatre Arts and English from the University of San Diego and is currently an MFA candidate in UCR Palm Desert’s Low Residency Program for Creative Writing, where she studies fiction and playwriting. She was also the Drama Editor for The Coachella Review’s Summer 2022 issue. Her previous works can be read in The Alcalá Review, Kelp Journal, Little Thoughts Press, GXRL, Grande Dame Literary Journal, and Longleaf Review. Her Twitter is @luree_s.