TCR Talks with Jim Ruland

by Jenny Hayes

In Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, Jim Ruland chronicles the history of legendary independent punk/alternative rock label SST—an epic tale filled with rock-and-roll thrills, chaos, bad behavior, good times, shady financial maneuvers, lawsuits, cross-country tours, and many other twists and turns with an eclectic cast of misfits. Started in 1979 by Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn, SST has churned out nearly four hundred releases, including influential records from now-well-known bands like Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Bad Brains, and Sonic Youth. The label and its owner are known for eclectic taste and a nonconformist, confrontational attitude; a glance at the table of contents gives an idea of the range of its antagonists, with each chapter labeled “SST vs.” [blank]—a band, label, scene, or concept (“Hollywood,” “Hardcore,” “MTV,” and even “Death”).

Ruland’s a natural fit to tell this story, given his long history of writing about punk and pop culture in Razorcake zine and elsewhere and his recent double whammy of punk book collaborations, Do What You Want, with Bad Religion, and My Damage, with Keith Morris (founding member of Black Flag, Circle Jerks, and Off!). Ruland has also published the novel Forest of Fortune and short story collection Big Lonesome, and he co-authored Giving the Finger: Risking It All to Fish the World’s Deadliest Sea with Scott Campbell Jr. of Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch. When I talked with Jim, he happened to be in Hermosa Beach, right where the SST origin story takes place.

The Coachella Review: How did this project start?

Jim Ruland: I personally came to be interested in SST Records late in life—largely through working with Keith Morris on his book, My Damage, and also from having spent some time in the [Los Angeles] South Bay. I lived in a couple places in Manhattan Beach and Playa del Rey, and when you’re in the South Bay, it’s different. You’re twenty minutes from a freeway, which is a long way in Los Angeles. And as a result, there’s a little bit of a bubble. People who are from there tend to stay there. When you’re here, you tend not to leave. I kind of fell into that, and I had to work against it. I would go to punk shows and stuff, but I was more into the underground stuff. I always thought of SST as one of the big labels. But once I started working with Keith, I was really interested in how the label formed, with Black Flag, and where it went from there.

TCR: So when did you decide “okay, this is a book”?

JR: Well, it wasn’t my idea. I was approached by an indie publisher, and at first, I was convinced it was a bad idea. Because I’d worked with Keith, and I knew that he had battled Greg Ginn and been to court with him. And there were a lot of things for his project he couldn’t tell me because he was embroiled in this nasty legal thing. So I thought, That’s a nonstarter. I wouldn’t want to work on something like that.

But Keith was able to separate the music from the label. And he said, No, the records that came out on that label are amazing, and someone should tell the story, and you should do it. And I thought, Wow, that’s really big of Keith, for one thing. And it got me thinking about it. Things didn’t work out with that publisher, so I took the project to the publisher that put out Keith’s book and who put out the Bad Religion book that I’d finished. And here we are.

TCR: You interviewed a lot of different people as part of your research, but I don’t think you actually talked to Greg Ginn. What was it like writing this book where this one figure is so central, for better or worse, but, from what I can tell, wasn’t directly involved?

JR: He was not involved at all. He actually responded to my interview request by saying that he retired from interviews. So that was helpful, in the sense that I knew that wasn’t coming. And yeah, it’s a little bit like The Third Man, right? I mean, he is a central figure of the story. Though, for the first hundred pages or so, it’s more about Greg Ginn, the guitar player, than Greg Ginn, the record label owner.

But I didn’t bring any beef or baggage to this story. Black Flag wasn’t my favorite band, or any of them; I liked the music, but none of these bands were my favorite band. I wasn’t coming in hot to this project, like, I’m gonna get to the bottom of how so-and-so got screwed, or how so-and-so’s getting a bad rep, or any of that. I just wanted to tell the story. And I also didn’t want to get into the personal side of things. Because when you scratch the surface of the story, you have a lot of people who have very white-hot emotions about SST Records. Either people are fanatics, fans of the music, so that fandom extends to loyalty to the label, or you have people who have been burned and are very, very bitter. I felt like either one of those poles would be harmful to the project. So I just tried to sail right down the middle of that. Not as an impartial observer, because, as you know, I have some pretty strong opinions about some of the music that came out. I don’t offer up the pretense of objectivity; it’s definitely my take on it. Someone else writing it would have a different take and talk to different people and reach different conclusions.

TCR: That makes sense. There were definitely places in the book where you added your own thoughts to give more context to the story or put things in perspective, even just giving your own descriptions of what the bands sounded like. But a lot of it is told in a more straightforward, sort of journalistic style, like you’re reporting the story. Did you think a lot about how much to interject your own personal take versus trying to keep it more objective?

JR: Well, it’s definitely my take on a lot of things. I mean, I let my own curiosity and my own interests guide me. But there was also the danger of too much research and talking to too many people, or going down the rabbit hole of trying to catalog every single album. Because SST was remarkable in its fluidity. There are so many genres of music represented. And I think that follows Ginn’s personal interest and aesthetic taste in music as he grew and developed. The thing is, there is a lot of subjectivity about the why, like what caused the label to act a certain way. And for most people, it becomes very personal. And that was something I wanted to stay away from, also for legal reasons. I don’t want to provoke someone who has already demonstrated being extremely litigious.

TCR: Yeah, you even talk about several different times where there was an interview or article or something about the label and Ginn was like, Why aren’t you telling my side of the story? With Negativland, with a fLiPSiDE interview early on . . . He has a history of wanting his part of the story told, so it’s interesting that he declined to be involved. Do you have any idea what he thinks about the project?

JR: I don’t. I think if he looks at it with a clear head, it’s a celebration of the music. And that can’t help but benefit the artists who came out on that label. Some of them are no longer with SST, but some of them still are.

TCR: Yeah, and he has used song titles to take jabs at people . . . I was wondering if there might end up being one with a pointed remark about you!

JR: I mean, the guy holds grudges. It could be. But at the same time, I just don’t know. It really has to do with his ambition for the label. And there are bound to be inaccuracies that will be pointed out to me, and I hope that people do so that people continue to talk about what really happened.

TCR: Going back to the research and what you said about falling down the rabbit hole—I mean, you did original interviews and also a ton of research through books and other publications. The footnotes and bibliography are massive. How did you find the right balance of getting the information you needed, but not letting it go on forever?

JR: There’s a lot of answers to that question. The first part is I’ve been writing for punk zines for a long time, and I love punk books. And it’s always disappointing when a book comes out and for whatever reason it doesn’t have an index. Or it doesn’t have attribution as to who said what. Sometimes there’s a feeling like, Well, it’s punk, there’s no rules, we just tell our stories. But we’re talking about an art form that’s been around for close to fifty years now. And people do serious scholarship on it. I just wanted the people who had done the work to get recognition for it, even if it was someone who may have been a teenager at the time, with a zine that they never thought was gonna survive. That’s my own bias as someone who has spent a lot of time in the van recording bands before their gigs. So that was my own personal view on that.

And I also knew that, especially for the people I was not able to talk to, I wanted to know what they were saying at the time that things were happening. I didn’t want to just run through revisionist takes on things. So I thought it would be more interesting to see what Chuck Dukowski had to say to someone who was pointing a microphone at him in 1981 as opposed to digging up something that was a bit more recent.

TCR: With all that research, what were some of the challenges of trying to synthesize it into one narrative?

JR: One of the biggest challenges was which bands to give the most attention to. I tried to narrow it down to the bands that had the biggest impact on the label, not my favorite bands, not the ones that I thought were the coolest but how did they shape the label? How did they grow the label, or take it in a new direction, or take it in a negative direction? So that meant that I had to leave a lot of stuff out that I did not want to leave out.

For example, Saint Vitus is kind of an outlier in the SST family because they’re a real hard, heavy, sludgy band. A heavy metal band, but in the Black Sabbath mold rather than what was popular in 1986 or 1988. And I would have loved to have just gone into that. Like, what was up with these guys? Why that style of music then? But because they were nice guys and local, they often got the short end of the stick. They would record an album and it would come out a year or two later. So their impact on the label was not as massive as some of the other bands. But it’s interesting because their impact on the genre of doom metal is enormous. They’re considered one of the godfathers of doom. And trying to get original pressings of those records is really hard because they’re extremely valuable. It took a long time for people to see the value of what this band was doing. Greg Ginn and SST saw it right away. So they’re definitely part of the story, but they’re a great example of someone that I could just totally geek out on for dozens of pages, but I had to restrain myself.

TCR: What surprised you as you did the research? Were there things that you had one idea about that turned out to be a different way?

JR: Well, that was everything. You think you know something, and you only know a little, or maybe you misremembered, or maybe you didn’t know . . . The biggest surprise for me was OXBOW. They come in at the end of the story. I think I called them the last great record that SST released. It’s called Serenade in Red, and the first time I listened to that record it blew my mind. There’s nothing else like it in the catalog. And when I got into the story of how the band came about, who they worked with, and how most of the members were in a hardcore band, in Stanford of all places, it was absolutely fascinating. And the singer, Eugene Robinson, who has written books himself—someone someday will write an amazing book about his life, because he’s an incredible character in American music. They did a picture disc with Kathy Acker! They just did really cool stuff. Apparently, they’re signing with Ipecac, which is Mike Patton’s label. I think they’re going to rerelease their catalog, or put out new music, or both. I really hope that brings them a wider audience.

TCR: I’m not familiar with OXBOW, but now I’m gonna have to check them out. My biggest surprise was probably Nancy Pelosi’s daughter being an intern with SST. Either that or Greg Ginn having like eighty cats. That was a direction I didn’t see coming.

JR: Yeah. Unfortunately, the “benefit for cats” show was kind of a jump-the-shark moment.

TCR: As you were putting the book together, how much did you think of a certain kind of reader, or how much knowledge the reader would have about the label and the scene? There are people who are deeply versed in this stuff who are going to read it, there are people like me who have some familiarity, but don’t know all the ins and outs, and there are probably people, especially younger people, who are coming in without knowing much about it at all. How did you decide how much to explain things versus assuming the reader might have some familiarity?

JR: Well, what I learned when I was working with Bad Religion on their book is they had a long career with seventeen albums and lots of other different projects, and I would meet diehard Bad Religion fans and very quickly come to the conclusion that even the most hardcore fan of this one band didn’t know the whole story. That experience taught me that I really can’t assume that I don’t have to talk about something because everybody knows. Maybe not! So I really set out to tell the story of SST as thoroughly as possible so that people who were not bringing much knowledge to the story would understand it.

One of the first books I read when I was putting together my proposal was Michael Azerrad’s Our Band Could Be Your Life[: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991]. Dan Ozzi recently described it as a punk rock bible. It’s something that came out like twenty-something years ago and people still read today. It’s still in print, and young people read it. And I think that I was looking ahead and thinking, Man, this label started in the ’70s. The people in this band are not gonna be around forever. I’m not gonna be around forever! So I didn’t want it to be something that just a handful of SST insiders or hardcore record collectors would get. Like a bit of trainspotting: here’s some stuff you didn’t know. I tried to make it for a general audience and tell the story of the label so that it will hopefully last more than one publishing season. And maybe as people come back to me and tell me more stories and more information, and more things happen to the label, perhaps it can be expanded or somebody else can write the next chapter, or the rebuttal to this. I felt like it was a piece of the conversation that I really hope continues.

TCR: There are places in the book where you comment on some of the casual racism, sexism, homophobia, or whatever, some of which seemed like it was more just to be outrageous or antagonistic, in a way that was pretty common at the time. I mean, sometimes it was meant, but there was a lot more tolerance for “you’re wearing a swastika, but you’re not really a Nazi; you’re just trying to be shocking.” And today, we have a really different take on that. How much were you thinking about that shift in perspective, or putting that kind of thing into context?

JR: What’s interesting is that when I wrote the proposal for this book, I outlined the different areas, and it was all mainly about the different bands. But there’s one chapter that was “SST vs. the LAPD.” And as I was working on that era of Black Flag, it was during the pandemic and during a lot of the police protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. It was an inescapable thing. Here was this thing this band was dealing with, literally being persecuted by the police. And how little has changed from [former LAPD Chief of Police] Daryl Gates’s racist police practices and how those practices set the stage for so much unrest in the future. So that was something I was very much aware of.

But I was also thinking if I’m going to talk about that, then I also need to talk about some of the warts, the ugly side of things. If something was misogynistic, I wanted to call it out. If something was homophobic, I wanted to call it out. That was very important to me. Growing up in the ’80s, there was a lot of homophobia, not just in the air but in culture and politics. And that was very different from, like, Oh, let’s wear a swastika and piss off the normies. That was real. And so I felt like it would have been irresponsible to not point it out where it happened. It felt like that was my responsibility to do. And like you said, modern-day readers bring a lot more awareness to that kind of thing. I had read an article about Bad Brains, part of their reissue campaign for some of their records, and the article kind of glossed over some of the homophobia that was prevalent in the band. And the readers let the writer and the publication have it in the comments, and I was very gratified to see that. It’s not about persecuting people for something they’ve apologized for; it’s about acknowledging that it happened.

TCR: You’ve written in a lot of different genres—fiction, reviews, interviews, collaborations with different people telling their stories, and now this book, which is this big, sprawling history of the label. What are the similarities that come through for you when you’re working on a piece of writing, regardless of the genre or style?

JR: I think it comes down to—what am I curious about? A lot of my fiction kind of falls into a category of “wouldn’t it be cool if.” And then creating a scenario. And with the nonfiction, it’s kind of reverse engineering that. Here’s this cool thing; how did it get to be that way? And like a lot of people, you’re just curious about more than one thing.

My decision to take a project also has to do a lot with the experiential side of it. Like, I wrote a book with one of the captains who was on Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch. And I didn’t write that book because I wanted to cozy up to a reality television star. I took that assignment because I thought it might take me out to Dutch Harbor, Alaska. And it did! And that was the really exciting part for me, to be in fucking Alaska!

TCR: It’s interesting because I know in your newsletter you talked about how most of the research for this book took place during COVID. So that probably wasn’t as experiential as you’d hoped, just because everybody was stuck at home.

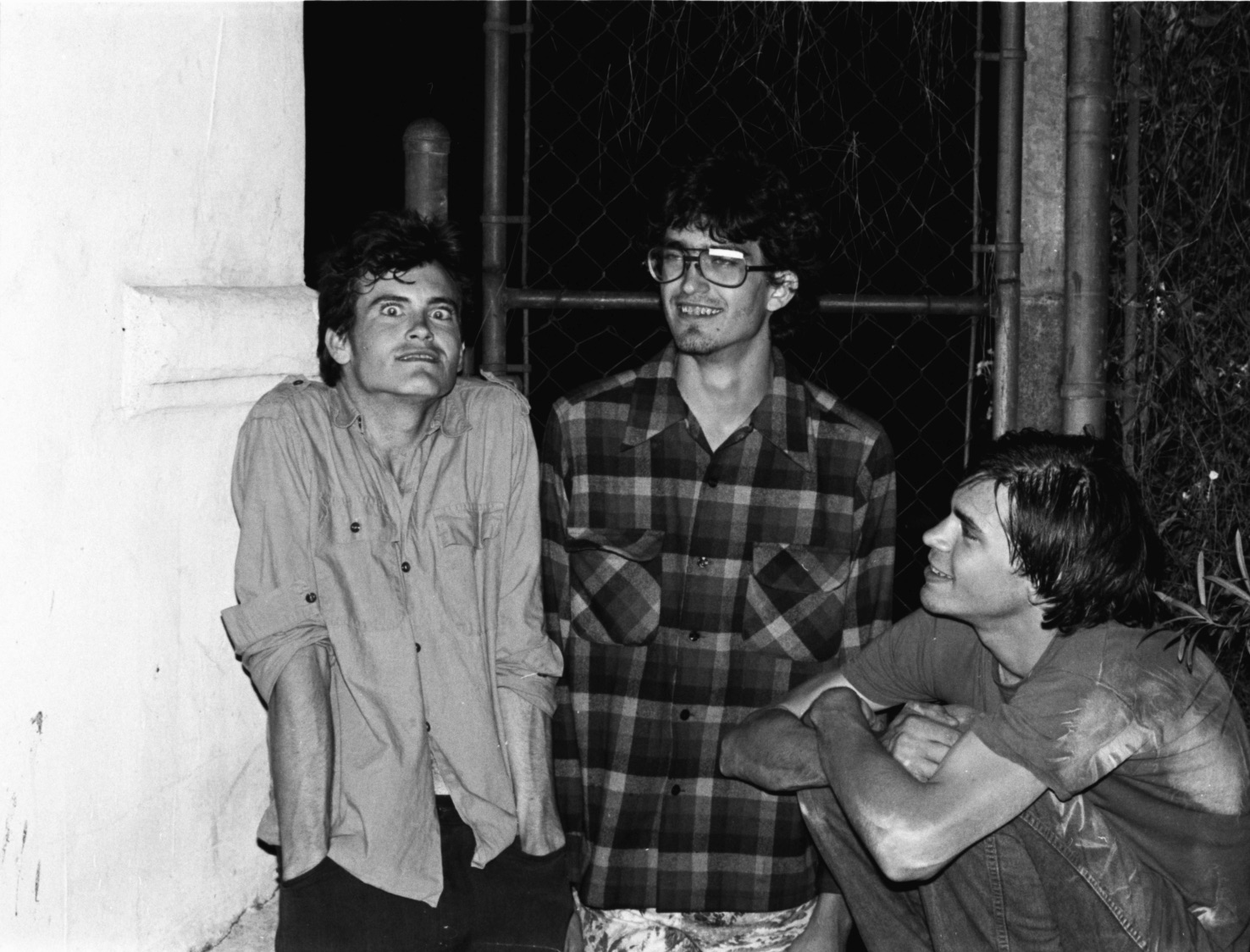

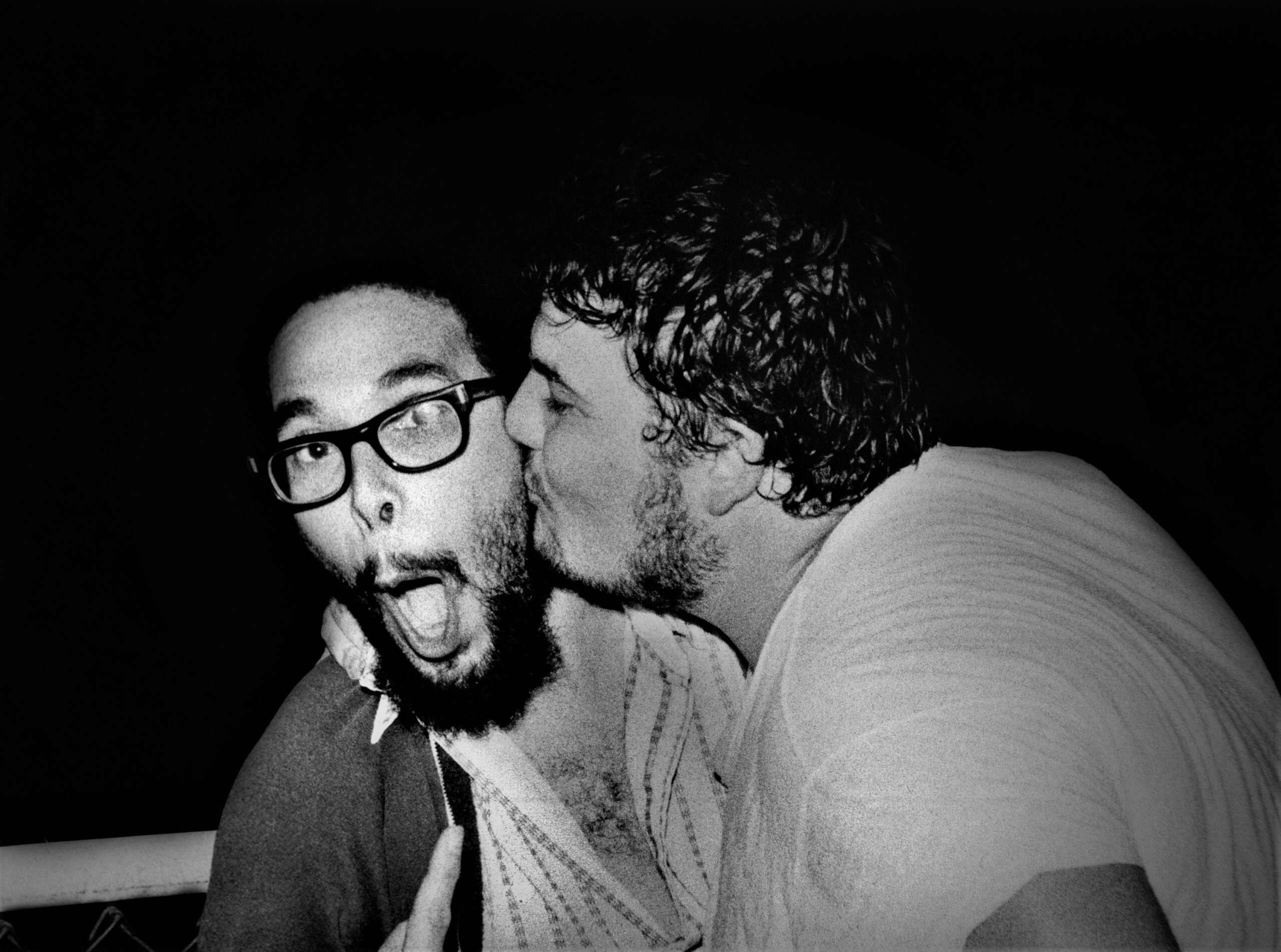

JR: It’s starting to happen now, in the sense that I’m meeting some of the people that I interviewed or that helped me with the project. That’s been really rewarding. I mean, I’m in Hermosa Beach right now, and last night, I was at an event for a punk photography book and Earl Liberty from Saccharine Trust and Dez Cadena from Black Flag were both there. So that was really exciting.

I think you’ll get a kick out of this: I wrote a short story, probably the first one I’ve written in six months or so. I decided I’m gonna write a short story that’s set in this world of rock and roll. And it was a terrible story. The first draft was . . . you know how usually you finish something and you’re like, okay, this needs work, but there’s something about it you feel, like, man, I’m really on to something here? There was none of that because I realized the whole story takes place on the phone. Which has been my rock and roll experience for the last two years. It’s been on Zoom calls. And that is a very sad thing.

TCR: Yeah, nobody wants to read about that [laughs]. What’s next for you? Are you planning to do more books on the music scene, or have you had enough at this point?

JR: Well, I’m working on a book with Evan Dando of The Lemonheads. Which, depending on how well you know The Lemonheads, is either a radical departure or fits right into that groove. Because The Lemonheads started out as a punk band, I like to remind people. And Evan Dando is still very much a larger-than-life character. So I think it fits right in with all of that. But I’d love to work on a biography or another kind of character, like a filmmaker or a visual artist, maybe even another writer. When you start writing a book, you never know what you need to know. But each one, the writing of it gives you confidence to try new things. So I’m really open to something new.

And then I have a novel I’ve been working on for years called Make It Stop. It’s set in Los Angeles in the near future, in a world where if you can’t pay your hospital bill, you don’t get to leave. And our hero works for an underground organization that busts people out of these prison-hospitals. It’s kind of a dysfunctional vigilante story.

TCR: Is there anything else from a craft perspective you think might be interesting to our readers?

JR: Well, I think that this career that I’ve stumbled into as a “punk whisperer,” as my friend likes to jokingly refer to me, was borne out of my passion for zines. And I’ll let you in on a secret: no one gets into zines for money. I think it’s really interesting in that there’s all kinds of ways to be a writer. And we’re always being told it’s all about platform: if you want a book deal, you need a platform. And there’s some truth to that, and there’s some cynicism to that, and there’s a lot of bullshit to that. But those people with the platforms? They need writers, too. It can be a very fascinating and entertaining way to make a living.

Jenny Hayes lives in Seattle and is a graduate of the low-residency MFA program at UC Riverside-Palm Desert. Her fiction has appeared in Hobart, Geometry, Spartan, Jenny Magazine, and other interesting places.