Book Review: Stuart Kells’s “The Library”

BY A.M. LArks

It’s hard to say that The Library by Stuart Kells is about a single library, or even the idea of a library as we have come to know it—a collection of books that the public can borrow. Stuart Kells’s library is both a historical compilation of well-researched facts that informs the public about the origins of our notion of the “library” and the examination of those assumptions.

Kells takes the reader from the first Australian’s oral history and storytelling traditions to the banks of ancient Egypt. Kells annotates the influence of the Greeks and then the Romans on libraries, knowledge, and a love of books before dropping us into medieval times, where the church ruled library collections and monks were the saints in the bibliophile’s Rolodex. Kells then vaults forward with the invention of the printing press, the Renaissance, and the Industrial Revolution. This is where Kells’s narrative drifts; compared to the comprehensive coverage of the libraries of antiquity, there is very little about the modern library.

Where Kells shines is when he dives into the underlying notions of a culture’s need to collect books and applies them to our current culture. Why else write a book for the general public about libraries? If this were merely a retrospective, a history book would be sufficient.

In his opening chapter, Kells addresses the idea of a library by positing that a library need not have any books. “If a library can be something as simple as an organized collection of texts, then libraries massively pre-date books in the history of culture. Every country has a tradition of legends, parables, riddles, myths, and chants that existed long before they were written down.” As an example, Kells documents Dreaming tracts, or tjurunga lines, by the Arrernte people, a group of first Australians. “Every Dreaming track is inherently multifaceted, blending animate and inanimate entities, past and present, fact and belief, ground and sky.” These were not considered to be books until they were compared to the Western canon in 1971 by little-known author T.G.H. Strehlow. It was not until British author Bruce Chatwin published Songlines in 1987 that Dreaming tracts become part of the worldwide vernacular.

By its inclusion here, Kells is arguing that Dreaming tracts—along with other oral  histories—should have been included in our libraries all along because a library is only an organized collection of texts. What is lacking is a discussion about what in our modern lives mimics a similar inclusion? Do messages on Facebook or undeleted text messages merit inclusion in a library? Should that cat meme be sitting next to Shakespeare’s First Folio in the Larks Home Library?

histories—should have been included in our libraries all along because a library is only an organized collection of texts. What is lacking is a discussion about what in our modern lives mimics a similar inclusion? Do messages on Facebook or undeleted text messages merit inclusion in a library? Should that cat meme be sitting next to Shakespeare’s First Folio in the Larks Home Library?

Kells examines more than what texts are or what should be included in our libraries with questions like: Who uses libraries? (In every period it was mostly scholars.) Who is allowed to look after our libraries? (All sorts of people. Many unqualified. Some of the worst book thefts came from those with the greatest access.) Or can a library have too many books? (Yes. “Despite the labels on the outside of Alexandria’s scrolls, readers struggled to find specific volumes – there were just too many books.”)

But what is lacking is a direct discussion on the purpose of a library. Is it to preserve books or to offer books of use? For a bibliophile like Kells, the idea that the Amborsian Library in Milan “…in the seventh century, swapped a selection of ‘more useful’ modern books for part of Bobbio’s ancient library [which included a large group of Italian pre-Caroline manuscripts]” is a travesty. For Kells, this information is tragic due to the loss of the historical record, which can be read in his admiration for the monastic efforts during the Middle Ages: “Indeed, the manuscripts that accounted for a large proportion of the monastic effort now account for a large proportion of the extent of the Middle Ages –and of our knowledge of what delighted, appalled, and terrified the people of the time.” But how is the lack of pre-Carolinian manuscripts relevant to today’s culture? What have we lost by not knowing what we don’t know?

This idea of preservation versus function underlies several of Kells’s so-called book crimes, like chop-shopping manuscripts and bindings for parts or the selling off of manuscripts to bookbinders and transmen for the value of their vellum and parchment. (Kells should definitely stay off Etsy, where books are often sacrificed to the crafts gods for any number of personal or home accessories!) As a self-proclaimed bibliophile, a lover of books, the assumption is implicit that books should be preserved. However, if the function of a library is not preservation but function, then the reducing, reusing, and recycling book or the mass liquidations of books are not criminal but merely economical decisions.

Books have always lingered in the purgatory between these worlds, mainly because they skirt the intersection between beauty and utility as exemplified by the hand- lettered illuminated manuscripts or gem-encrusted bindings of antiquity as opposed to the books chained in several libraries to prevent theft. But what is the collective drive to amass collections of information? Why does it exist? In the discussion of past great civilizations (like the Chinese dynasties or the Roman Empire among many others), it becomes apparent that this drive is one associated with the information inside the various tomes, bringing to mind the familiar adage that knowledge is power. But why, with the invention of the internet, do humans still strive to amass libraries? Kells defines the internet as a series of inscrutable monologues that are “without boundaries and selection and navigation…,” which render such libraries useless.

lettered illuminated manuscripts or gem-encrusted bindings of antiquity as opposed to the books chained in several libraries to prevent theft. But what is the collective drive to amass collections of information? Why does it exist? In the discussion of past great civilizations (like the Chinese dynasties or the Roman Empire among many others), it becomes apparent that this drive is one associated with the information inside the various tomes, bringing to mind the familiar adage that knowledge is power. But why, with the invention of the internet, do humans still strive to amass libraries? Kells defines the internet as a series of inscrutable monologues that are “without boundaries and selection and navigation…,” which render such libraries useless.

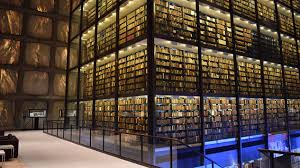

Ultimately, though, Kells concludes libraries are “much more than the accumulations of books, the best libraries are hotspots and organs of civilization; magical places in which students, scholars, curators, philanthropists, artists, pranksters, and flirts come together and make something marvelous.” Outputs that are not measured in modern clinical managerial evaluations are “…places of solace and education, sources of nourishment for the human spirit.”

A.M. Larks writes fiction and nonfiction. She has performed her stories at Lit Up at Town Hall Theatre in Lafayette, California. She contributes reviews and interviews to and is a reader for The Coachella Review. She earned a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, a Juris Doctorate, and is currently pursuing her Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts from the University of California–Riverside Palm Desert’s low-residency program. She lives in Northern California.