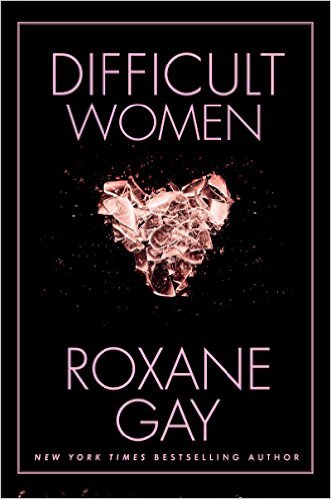

Book Review: Roxane Gay’s “Difficult Women”

By Jenny Hayes

Roxane Gay’s Difficult Women is a relentless and thrilling read. As in much of Gay’s other work, particularly her novel An Untamed State, there is no looking away from brutality, yet moments of grace, beauty, and humor serve as striking counterparts to the more unsettling passages.

Roxane Gay’s Difficult Women is a relentless and thrilling read. As in much of Gay’s other work, particularly her novel An Untamed State, there is no looking away from brutality, yet moments of grace, beauty, and humor serve as striking counterparts to the more unsettling passages.

In these twenty-one stories, women negotiate problematic relationships, search for love and comfort, and try to cope with pain. While echoes of one story often arise in another, the overall effect is not one of repetition—Gay’s characters and plots are anything but predictable—so much as variations on a theme: women attempting to navigate their complex lives. This alone, perhaps, is enough to make them “difficult women”—though “difficult,” like “crazy,” is mostly in the eye of the beholder. The title story includes a line that could function as a sort of thesis statement for the book: “Honey, you’re not crazy. You’re a woman.”

The styles of these stories are varied, with a few of them verging into the unreal. In “Requiem for a Glass Heart,” a stone thrower marries a woman made of glass: “He was the first man who did not see through her.” Another story, “Water, All Its Weight,” involves a woman who is literally followed by water everywhere she goes. Stains form on ceilings above her, rainclouds circle wherever she walks. Understandably, this makes her difficult to live with, and she is abandoned first by her parents, then her husband. It’s a fascinating tale in itself, but also a moving metaphor for anyone who is apparently impossible to love.

Many of Gay’s protagonists have gone through some sort of traumatic experience in their near or distant past, and Gay shows them grappling with the aftermath, trying to find some kind of solace that lets them survive. Sometimes, this solace is understandable. In “North Country,” previously anthologized in Best American Short Stories 2012, the narrator slowly lets her guard down with a man who shows her that he’s strong enough to love a difficult woman. And in “I Will Follow You,” two sisters abducted as children turn to each other for comfort. “My sister was the only place that made sense,” the narrator says shortly after they are rescued. Years later, they still insist on sticking close together, regardless of the impact on the rest of their lives and those of the people around them.

More often, Gay’s characters find what they need in places which seem less expected, even unacceptable. In “Break All the Way Down,” a woman whose young child was killed in an accident pulls away from her kind, loving husband. She loves him deeply and knows he is suffering too, but the logic of her pain demands something different. “At a bar I found an angry man who would hit me,” she says, revealing the brutal transaction of replacing an overwhelming pain with one that is simpler. “Every time that man sank his fists into my body, I could breathe a little.” In “Baby Arm,” the narrator is dating a window-display designer who brings her gifts of baby mannequin limbs. This begins to win her over, though what she truly needs, she gets from her best friend, Tate, and the all-girl fight club they take part in. “Ten of us who are pretty and fucked up, girls who keep their ugly beneath the skin where it belongs, even though sometimes, it’s hard to keep it all in.” After they all beat the shit out of each other, she and Tate smile at each other while eating greasy chicken, and she confesses, “This is the most I will ever love another person.” The situations in the stories can be unsettling, yet I found myself repeatedly drawn to the honesty of the characters as they attempt to define and satisfy their desires and needs.

Throughout the book, Gay’s prose is lovely to read. Her sentences are stark and direct, their simplicity and conversational tone often belying the emotional weight they deliver. When the protagonist of “Break All the Way Down” manages to find her way back to her husband, their kiss isn’t just a kiss, it’s one that tastes “like the whitest heat of a fire closest to the ground where most things burn.” In “Noble Things,” a tale of an imagined future in a divided America—first published in 2014 but startlingly relevant to the present moment—Gay describes a troubled couple’s Florida honeymoon in happier times: “Enjoying the heat was decadent and they were decadent and there was no regretting it.”

Gay’s protagonists may be “difficult,” but they are not difficult to empathize with or to root for. While reading the book, I mused to myself that the collection could just as easily be titled “Damaged Women,” or just “Women.” After all, most women live with the aftermath of some kind of trauma or loss; as the title story attests, dead girls are the only ones at peace. But not all women behave like Gay’s characters, who are “difficult” largely because they refuse to comply with the unwritten rules to be compliant and silent in the face of pain, violence, and loss. They certainly aren’t role models, nor are the stories didactic in nature, yet there is something admirable in the way they choose to put their needs first, regardless of whether those needs make sense to anyone else. As the book’s dedication proclaims, difficult women “should be celebrated for their very nature.” Gay’s stories about them merit the same celebration.

Jenny Hayes lives in Seattle and is an MFA candidate in the low-residency creative writing program at UC Riverside–Palm Desert. Her fiction has appeared in New Flash Fiction Review, Litro NY, Jenny Magazine, Spartan, and elsewhere, and her chapbook “Dear Rosie AKA Ro-Ho-Zee AKA Rosarita Refried Beans,” featuring an illustrated story about junior high and David Bowie, was published in 2014 by alice blue books.