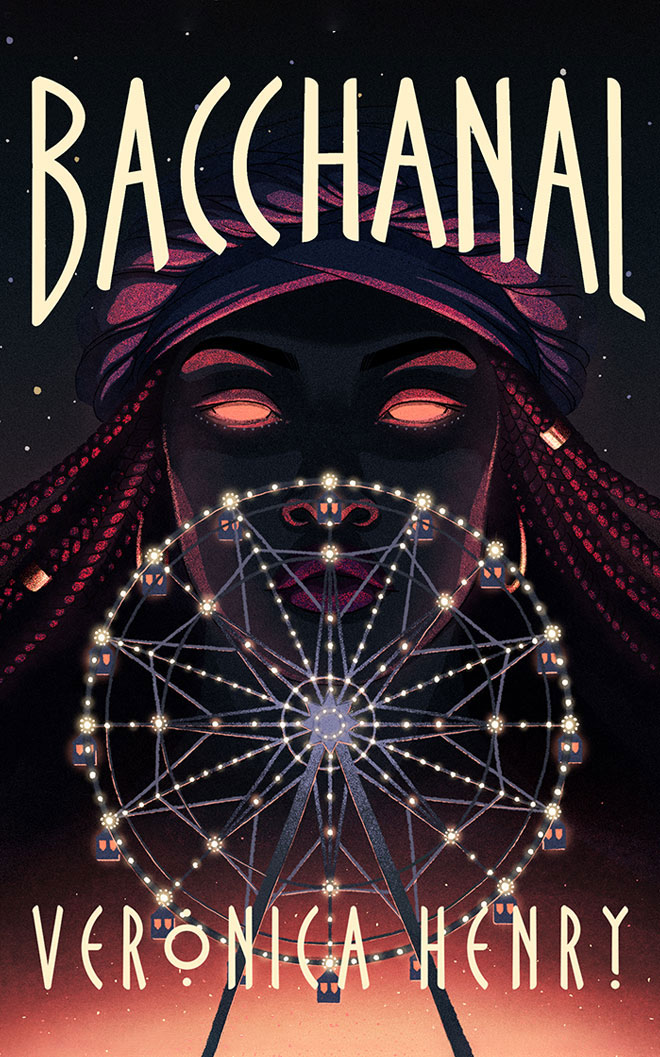

The Coachella Review is honored to present an excerpt from Veronica G. Henry’s debut novel, Bacchanal. This novel is a fantasy and historical fiction set in the Depression-era South. Centered on Eliza Meeks, a young Black woman with the power to communicate with animals, the novel takes the reader on a journey of self-discovery and acceptance as Eliza joins a traveling carnival with a sinister secret. Unbeknownst to Eliza, she is being searched for by an evil spirit, Ahiku, whose goal is to destroy Eliza before she can come into her true power. With a cast of diverse characters, Henry frames a moment in American history with varied and refreshing experiences not often seen in fantasy or historical fiction. Henry also integrates African culture and folklore into the story, creating a unique perspective for readers of speculative fiction.

“Hey!” Clay snapped his fingers in front of Liza’s face, bringing her out of her angry reverie. “If you don’t have nothing better to do than stare off and chew on your lip, do me a favor and find Malachi. Tell him the rest of his supplies are in.”

Liza was about to protest, but Clay had already moved on to handle the next emergency. The man lived in perpetual motion; she suspected he woke up in sweats from all the running he must do in his sleep. People who tried to stay too busy were only running from something they didn’t want to catch up to them. I wonder what Clay is running from. She rolled her eyes and set off to find Malachi.

He was right where Clay could have found him himself—outside his trailer, doing a series of stretches, movements she’d never recover from if she tried. Bent over at the waist, he stood slowly, as if he were stretching each bone in his back.

“You have finally agreed to join me in my morning exercises.” He grinned and, as usual when she looked upon a face so serene, all her troubles slipped away. His gaze was calm yet intent. “Something’s bothering you,” he said and then gestured for her to join him. “Sit.”

“I shouldn’t,” Liza protested. “Clay wanted me to tell you the things for your show have come.”

Malachi swatted the information away like a pesky fly. “In a minute,” he said again. “Sit.”

Liza complied like a sullen child hopeful that there might be a treat at the end of the sermon. When Malachi didn’t say anything else, only holding his head back slightly and letting the sun fall full on his face, she huffed—loudly. Well, she wasn’t going to say anything; he was the one who’d invited her to sit.

Finally, he said, “You are uncomfortable with quiet?”

“No.” Truth was, discomfort squirmed in Liza’s gut like week-old gumbo. “I don’t like to waste time.”

Malachi opened his eyes. “Whatever time you can manage to spend alone with your thoughts is never wasted. Care to tell me what’s clouding that face of yours with such consternation?”

Why should I? But something about Malachi wouldn’t let her turn her sharp tongue on him. She was surprised when she let the words spill out, explaining the amulet, her problem with sometimes killing the animals, her attempts at learning to control her talent with Ishe.

“You believe that there is no separation between the spirit world and ours? That they are always around us?” Malachi rested his hands on his knees and regarded her without a hint of judgment in his eyes.

Liza tugged on her braid. “My mother spoke of them . . . some.”

“Then you must know that they influence us in ways we don’t always understand.”

The man goes a long way around to making his point. She shrugged. “And what does that mean to me?”

“It means,” Malachi said, stretching out the last word, “that I’ve studied myth and religion from many cultures, and they all have some form of that belief in common. Answers are often right in front of us; you just have to tune your mind to the right station to find them.”

With this Liza perked up; she could almost see the path of where he was going. “And you know what the discs mean?”

“No,” Malachi said, gesturing with his chin. “What animals are carved on there?”

Liza recounted the elephant, the raven, and the badger.

“Hmm. And of your African lineage, you know nothing?”

She bit her lip in answer.

“Let’s try this. You ever heard of ancient Kush?”

Liza may not have read as many books as a man who’d been to college, but she’d read her fair share. “Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan,” she said.

Malachi beamed. “The birthplace of Kemetic meditation. Some say all meditation sprang from that practice.”

“Meditation?” That hadn’t been in any book she’d come across.

“Rest your hands in your lap and close your eyes,” he instructed. “Breathe deeply, count your exhales one to ten, then begin again. Let your mind wander, and if a thought intrudes, push it gently away until the image you want, what you seek, comes to mind.”

Before Liza could say that she had no idea what she was looking for, Malachi added, “You’ll know when it comes to you.”

Skeptical, she tried the exercise, breathing in and out, in and out. The stilt walker—what had that been about? She shoved that aside, only to have it replaced by an image of Jamey, the curve of his lips; she quickly pushed it away and started her counting over again. Mico, had she fed Mico? She pushed that aside as well. What kind of show would folks like? Ishe . . . she didn’t want to think about the way she felt around him.

“I can’t do this,” she said, opening her eyes.

Malachi simply said, “Try again.”

Liza gave him a side-eye, which he luckily couldn’t see, as his own eyes remained closed. She blew out an agitated breath and let her eyelids flutter closed again. It took some time, but soon, the sounds of the bustling carnival-setup activities around her faded away. The steady stream of mind chatter slowed some. For a brief, blissful moment, her mind was blank.

Unbidden images—not her own—played through her mind on a slow flicker: a raven soaring through the air, black, yellow beak, sleek lean body. She pushed the raven away, and it floated from her consciousness as if on a cloud. Then the elephant came, followed by the badger. Her heart beat faster in her chest, but she kept her breathing to a constant in and out; she had even stopped counting. She felt totally at peace.

The next image that floated into her mind was of a woman. Gray hair parted down the middle, her eyes round and intent, skin the color of charred wood. The woman’s name flooded her mind: Oya.

“It has taken you long to find me. I am your grandmother, goddess of winds and storms, of death and rebirth.” The woman’s voice rattled around Liza’s brain like a pinball before it settled. “I have a vision for you. A prophecy.”

A water buffalo thundered along on a wide-open plain. The beast stopped, dissolved into a pile of dust, and swirled upward into a tornado. When the tornado died down, Oya stood at the gates of a cemetery that stretched as far as the eye could see. The landscape changed, revealing centuries of death and destruction.

The badger spirit appeared then and took an ineffectual swipe at Oya. A burst of wind from Oya’s mouth sent him away. The raven swooped in, circling Oya’s head, and with a clap of her hand was zapped out of the sky with a lightning bolt. The elephant charged at her back, but she spun into a hurricane and tossed him into another place.

“You must make your peace with them. Accept the spirits. We cannot defeat our enemy without them,” the voice said. “And accept me.” Then Oya smiled at Liza and began to fade away.

“Wait!” Liza screamed aloud. “What enemy? What does all this mean? Who are you?”

“Liza.” Malachi was shaking her. “Liza, open your eyes.”

She jerked away from Malachi and scrambled to her feet.

“What the hell was that?” she shouted. “Are you playing some kind of trick on me?”

Malachi stood and regarded Liza curiously. “You had a vision?” He sighed. “Your path is not an easy one, then. Sometimes the spirits have plans for us that we don’t like. But when your path is laid out, you have to walk it. I only hope that you learned something that will help you in what you must face.”

Grandmother . . . huh. Ikaki had told her that they liked her because of who her grandmother was. Was this Oya her grandmother? She’d said she was a goddess. Liza deflated. She’d learned more, all right, but this business about her animal spirits and nameless enemies—why drop that on her and then disappear? “I understand more and am more confused than before I started.”

“It will become clear.”

“And what am I supposed to do until then?”

“Nothing,” Malachi said. “Live. The ancestors will call on you when it’s the right time.”

“Why can’t the ancestors stay dead and gone like they’re supposed to.” Liza made it more a statement than a question. She met Malachi’s eyes and hoped her own conveyed some sort of gratitude for him trying to help her, but she stopped short of thanking him. Before she turned to leave, Eloko appeared. The grassy dwarf with his menacing snout winked at her before she hurried off.