By Sara Marchant

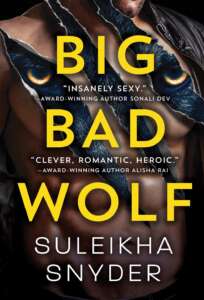

In Suleikha Snyder’s Big Bad Wolf, the world is full of strangers and strangeness, but it is recognizably our world. “Different,” she tells us, “unequal, but same.” The novel is set in the Divided States of America after the Darkest Day of 2016, where Sanctuary Cities are more than lip service and operate to protect the rights of the LGBTQ, women, and Black and Brown brethren as well as supernatural citizens, and the only unbelievable aspect of the story is a hero who prefers giving head to receiving it.

Joe, an anti-heroic (literal) alpha male, is awaiting trial when, Neha, a Sikh-American defense attorney/psychologist meets him. He has admitted to killing six Russian mobsters—he’s a “vigilante shape-shifter in a sanctuary city”—but he did it in human form and was only caught because he called in a tip about the container of women the murdered mobsters were trafficking. His means and motives baffle his new attorneys, as did his declaring himself guilty at his first (mis)trial. Neha’s two bosses, Nate and Dustin, best friends and partners but not lovers, are having a hard time preparing a defense based on the exact nothing Joe is giving them.

Joe’s obstreperousness is why Neha is brought in, and she assures him she’ll “break him,” in a pissing contest that seems counterintuitive in a doctor/patient context but perfectly acceptable in a dominatrix/submissive relationship.

Their attraction is immediate and obsessive, and animalistic on Joe’s part. The very first sentence is Neha thinking Joe looks like he wants to eat her—in a wolf-like way, not the sex act she later discovers is very much his passion. At their second meeting, Joe worries his wolf side has imprinted on Neha. Earlier, Snyder inserts a Twilight reference so you know it’s an inside joke. It’s a joke that works as it disarms, after all what kind of mass murdering werewolf watches Twilight?

Their attraction is immediate and obsessive, and animalistic on Joe’s part. The very first sentence is Neha thinking Joe looks like he wants to eat her—in a wolf-like way, not the sex act she later discovers is very much his passion. At their second meeting, Joe worries his wolf side has imprinted on Neha. Earlier, Snyder inserts a Twilight reference so you know it’s an inside joke. It’s a joke that works as it disarms, after all what kind of mass murdering werewolf watches Twilight?

The relationship of Joe and Neha is reflected and refracted by the swirling constellation of supporting characters, as diverse as a Fast & Furious film but deeper, richer; there are no caricatures or cardboard stand-ins in Snyder’s world. Even the villains, the Russian mobsters/ bearshifters, are humanized by the inclusion of Yulia, the head mobster’s sister who is in love with Danny Yeo, a beat cop who moonlights as part of an elite private detective agency dedicated to bringing down the mobster. This agency is populated by a lionshifter, a sorcerer, a vampire, and a human doctor everyone else fears for reasons never specified, except, perhaps, her beauty and scalpel-sharp intelligence. But Yulia-the-shifter loves her villainous brother even as she lives in fear of him, and of him finding out about Danny. In the Divided States of America, love and fear frequently go hand in hand.

The main characters themselves are so complex they are not always sympathetic. In the beginning, Neha recognizes that, sure, she was a little bit fucked up . . . and she refused to be fucked over.” And that’s before she screws Joe against a wall in an alley after helping him escape. The reader always roots for them. One is happy they’ve taken time out of their running to have dirty, public sex. Snyder makes sure we know they deserve it.

The supporting characters are also given what they deserve. They are layered, funny, charming and disarming. The vampire private detective annoys everyone with his chatter and innuendo even as they objectify and fantasize about him in turn; the only cis-hetero white male who isn’t a villain, Joe, tells the vampire he’s a great date. The villains have backstories and structure. They didn’t wake up evil; they were raised that way. But the true star of Big Bad Wolf isn’t any of the characters, as dimensional as they are. The world that Snyder created to house these people is deeply, starkly believable.

We aren’t told what year the book is set in, but we are told by Nate, the gay Jewish lawyer, that “in a country where presential term limits had vanished, abortions had been criminalized in more than half the states, and being different in any significant way got you sent to detainment centers. He’d grown up with ‘never again’ echoing in his ears, learning his family’s history over his Bubbe’s brisket, knowing firsthand what devastation creeping fascism could result in. He’d naively thought it couldn’t happen here. And yet here they were. Here we really are,” Snyder tells us when Neha first meets Joe in the prison interview room. “They lived in a country where a Black man could be choked to death for selling cigarettes, and a Sikh like her papa could be beaten for his turban . . . and here her firm was defending a white shape-shifter who’d been apprehended with nothing more than bruises.” Joe was a mass murderer when he was arrested, but he was a white man first. Sound familiar?

All of our good guy lawyers, doctors, detectives/resistance, whether shape-shifter or not, know that they owe what freedom they have to living in a Sanctuary City. “Large metropolitan centers like New York, Atlanta, and Los Angeles had taken the concept of ‘sanctuary’ one step further, almost operating as city-states to protect their vulnerable citizens.” They achieved this fragile impasse by giving up their right to privacy (a surveillance system of drones patrols the sky above the city). A life observed and contained (while on the run, Joe and Neha are careful to never leave New York city limits in order to avoid full-on fascism) is considered fair due to what happens outside the sanctuary. The camps lining the southern and northern borders were recently outfitted for supernatural citizens, although their primary targets were still people of color seeking asylum from situations even worse than those in the Divided States. Your choice in this world isn’t much of a choice at all. Unless, of course, you’re white. Joe is white, Neha isn’t. Their ending has to be happy because this is a romance, but it’s a romance set in a dystopia and Snyder isn’t going to cut the characters or reader any slack. It wouldn’t be realistic, nor honest.

Snyder tells us that in this world “the day-to-day for the average white human citizen was as it had been a few years before,” but for the Black and Brown citizens, the shape-shifter, the LGBTQ, the sorcerer, the vampire, and the refugees seeking asylum—their classification is instant and unchallengeable. Those who are “other than” white cis-hetero men are not even afforded second class status; they have no status. They might as well not exist. If not surveilled and contained, they disappear into camps and then just disappear. Neha and Joe, in the end, agree to work together toward something better for society, a world where they can be a couple, personally and legally. The ending hints at a sequel and gives every indication that Snyder’s realistic, animalistic, cranky characters are equal to the task of putting their world (and ours?) to rights.

Sara Marchant received her Masters of Fine Arts from the University of California, Riverside/Palm Desert. She is the author of The Driveway Has Two Sides, published by Fairlight Books. Her memoir, Proof of Loss, was published by Otis Books. She is a founding editor of the literary magazine Writers Resist.

Sara Marchant received her Masters of Fine Arts from the University of California, Riverside/Palm Desert. She is the author of The Driveway Has Two Sides, published by Fairlight Books. Her memoir, Proof of Loss, was published by Otis Books. She is a founding editor of the literary magazine Writers Resist.