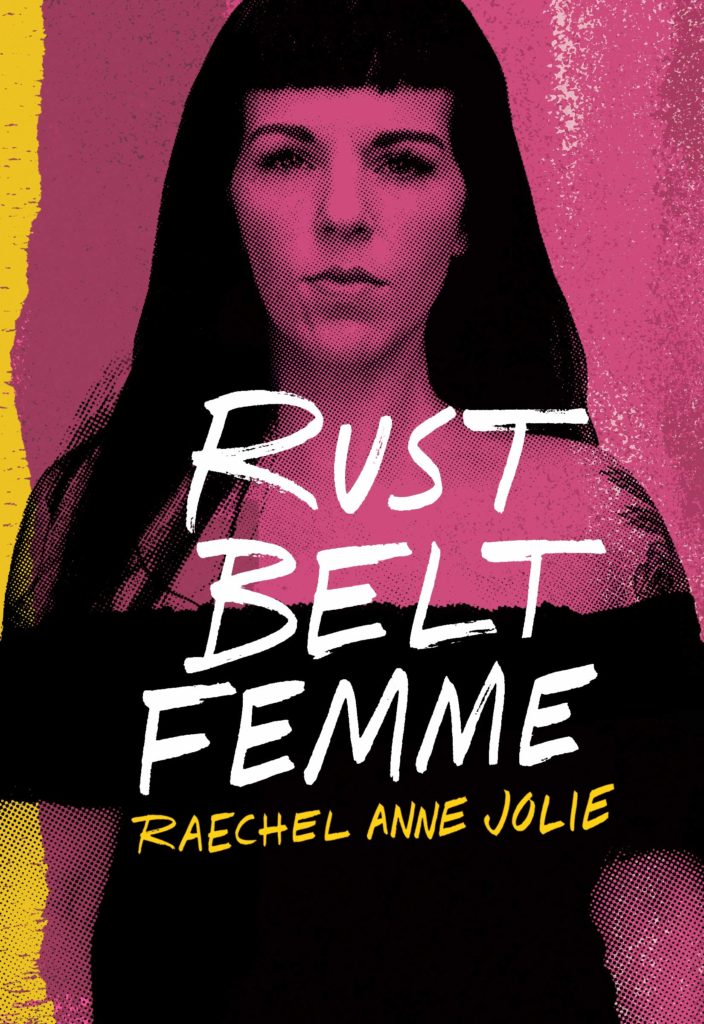

Book Review: Rust Belt Femme

By Briana Weeger

The brain often holds onto distinct and unexpected images and memories at the time of traumatic events. These memories may not make sense on their own, and they may seem disconnected from what actually happened.

The brain often holds onto distinct and unexpected images and memories at the time of traumatic events. These memories may not make sense on their own, and they may seem disconnected from what actually happened.

For Raechel Anne Jolie, in her coming-of-age memoir Rust Belt Femme, the unlikely memory is of lightning bugs. During summertime in a rural working-class Ohio village called Valley View, neighborhood children ran barefoot through unmown front lawns to catch fireflies. It is the fireflies Jolie recalls first when she thinks about her father’s accident.

One evening, Jolie’s father returned home from a late-night work shift and took out the trash. At the end of their driveway, where just days earlier Jolie played in the grass, her father was hit by a drunk driver.

Waking up from a coma with a traumatic brain injury, her father was greatly changed from the man he was before the accident. He once raced stock cars and took Jolie to the circus, but now he was physically aggressive and in a wheelchair.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#cc0000″ class=”” size=””]Jolie’s writing elegantly maneuvers between the different worlds that make up her identity. One moment, as a daughter in the trenches of poverty, she describes Sunday mornings at her house with her father’s race car crew filling the living room to watch NASCAR, swear, and make lewd jokes. In the next minute, as a Ph.D. graduate and professor, she explains the “complex personhood” of poor, white America.[/perfectpullquote]

In her memory of the lightning bugs before her father’s accident, a boy that Jolie had a crush on ripped the glowing bulb from the insect’s body, and with a blade of grass, made a ring to slip on her finger. The bottom end of the bug continued to glow, and she felt a complicated mix of protest and appreciation. This singular moment, tied to the trauma of her father’s accident, comes to symbolize much in Jolie’s journey. Jolie and her mother learn to resiliently carry on, and at the same time, still appreciate the magic and the glow that life can offer no matter how disembodied and difficult a time may be.

Amid the “white trash banality” of Jolie’s early years with race cars and beer-drinking men, her heroes became the “women who survived despite men’s absence.”

By the time I was five, I was surrounded almost entirely by resilient women … those lightning bugs fighting with persistent glow against the odds. They drank beer and swore. Their clothes were too big or too small. Many of them were tattooed. And always, always in their glorious excess, they showed up.

It is through these women that Jolie learned strength, and throughout the many trying times ahead, she carried with her this quality—the ability to find her way through, to learn the messy work of healing or compartmentalizing, and to move forward.

Soon after the accident, Jolie’s paternal grandmother, Agnes, didn’t think that Jolie’s mother was adequately caring for Jolie’s father. Agnes insisted that Jolie’s father move in with her and divorce Jolie’s mother. He did, and Jolie’s mother got sober, bounced between jobs, homes, and boyfriends, and learned how to be a single parent. Jolie’s life with her mother wasn’t easy, but it was full of love. Their relationship was fraught with fights, and tears—“the soundtrack of a lost husband, welfare checks, precarious employment. The ambient noise of the Valley was the soft hum of crickets and the raw cries of broken dreams.” However, following these fights were apologies, sing-alongs to Whitney Houston and Fleetwood Mac, and learning to use love as something that could repair the “hurt and immense fear in the face of scarcity.” Her life was ripped apart with the trauma of losing her father and the trauma of poverty. But through this, Jolie learned to always fall back on love.

Jolie’s writing elegantly maneuvers between the different worlds that make up her identity. One moment, as a daughter in the trenches of poverty, she describes Sunday mornings at her house with her father’s race car crew filling the living room to watch NASCAR, swear, and make lewd jokes. In the next minute, as a Ph.D. graduate and professor, she explains the “complex personhood” of poor, white America. She quotes sociology theorist Avery F. Gordon to explain that “it’s not wrong that poor, white America has its share of bigots, but it’s also not that simple. … Gordon describes this as the ‘complex personhood’ that means oppressed groups ‘suffer graciously and selfishly too, get stuck in the symptoms of their troubles and also transform themselves.’”

Jolie’s writing reflects the code switching she learned to do at an early age. Her grandparents and uncle lived in the suburbs outside of Tinkers Creek. When she would spend time with them, she noticed how their houses were spacious and clean and that they talked about literature and politics. “I knew the difference between Mom-and-me family and my broader family. I learned how to code-switch between my own relatives. It would serve me in so many ways after—code-switching from academic to white trash, and then back again; code-switching from queer to straight.” Jolie learned to navigate worlds and take with her the lessons of each.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”#cc0000″ class=”” size=””]Through all of the complexities and contradictions of her coming-of-age, Jolie learned that survival is interdependent. “We are as undone by one another, as we are made up of one another … this I have known since my days of sharing food stamps and not calling the cops on neighbors . . . it’s a beautiful reminder that we need each other.”[/perfectpullquote]

As a teenager, Jolie stepped into the alternative world of Coventry Road, Ohio—the Midwest Haight-Ashbury. Almost immediately, the art house cinemas, vintage stores, cafes and music clubs helped lead her towards the person she was already becoming. “Flipping through Cleveland Scene at Arabica Coffee house and circling the concerts I want to see. It feels so good to want things so desperately, that when you finally get them it’s like water on cottonmouth, like a sigh, or a bed when you’re exhausted. It’s the sinking deep relief when you know what you love with such certainty that it becomes how you make sense of yourself.”

Jolie found herself and she found belonging in the crowds at punk shows, and in the pockets of the outsiders and activists of Ohio. She volunteered with a group called Food Not Bombs (FNB) and further emboldened the outline of her political identity. “My politics gave me the only peace I can find when watching my hard-working mother dip further below the poverty line, when I grieve my queer Latinx friend who died in a jail cell … when I worry with my transgender partner about whether or not a doctor will treat him properly. It is deeply personal.”

Through all of the complexities and contradictions of her coming-of-age, Jolie learned that survival is interdependent. “We are as undone by one another, as we are made up of one another … this I have known since my days of sharing food stamps and not calling the cops on neighbors … it’s a beautiful reminder that we need each other.” The hard times Jolie faced also brought her the beauty of togetherness. And this togetherness taught her that despite not being set up for success, leaning into love and showing up is all the more powerful. The teased hair, the tattoos, and the excess came to not only shape Jolie’s relationship with femininity but represent strength against the odds.

In her prologue, Jolie explains that her story is one that is made up of many fragmented small stories. “Trauma has a way of mixing up the beginnings and middles, of never feeling an ending to any of it … and so my story is like this. Flashes of my early life, sliding against the hindsight that helps you tell the story better.” What is truly beautiful about the stories in her memoir is that it is Jolie stringing together glowing bulbs of experience into the strong queer femme educator and activist that she is today. Like the resilient Dolly Partonesque women who surrounded her, she learned to do her lips in the face of adversity, and like the glowing, disembodied lightning bug, persevered “in a way that is as beautiful as it is grotesque.”

Briana Weeger is a native of Southern California and is currently an MFA student in the low-residency program at UC Riverside. An alumna of UCLA and Brooklyn College, Briana works with underserved and immigrant youth using story crafting and storytelling as a means of self-discovery and empowerment. In her own writing practice, she is exploring the impact of often overlooked social customs with a mix of both fiction and non-fiction.

Briana Weeger is a native of Southern California and is currently an MFA student in the low-residency program at UC Riverside. An alumna of UCLA and Brooklyn College, Briana works with underserved and immigrant youth using story crafting and storytelling as a means of self-discovery and empowerment. In her own writing practice, she is exploring the impact of often overlooked social customs with a mix of both fiction and non-fiction.