BY: A.M. Larks

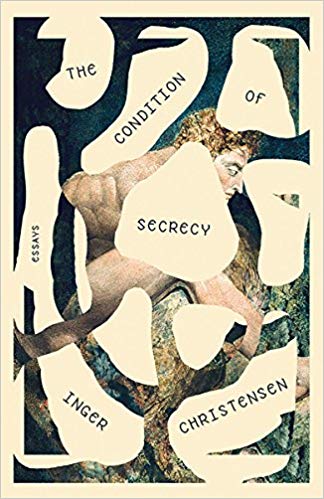

“For as human beings, we can’t avoid being part of the artistic process, where source, creation, and effect are inextricably bound together. Here in our necessity,” Inger Christensen writes in her collection of selected essays, The Condition of Secrecy, which contain, in part, her thoughts on writing and its fundamental role in human existence.

“For as human beings, we can’t avoid being part of the artistic process, where source, creation, and effect are inextricably bound together. Here in our necessity,” Inger Christensen writes in her collection of selected essays, The Condition of Secrecy, which contain, in part, her thoughts on writing and its fundamental role in human existence.

The heart of this collection lies in Christensen’s philosophies on writing, which comprise half of the essays, including the titular one. In The Condition of Secrecy, Christensen discusses a myriad of topics relating to writing and opens the discussion with what a poem is: “What we sense when we read a poem is the motions of the mind. Not only the poet’s mind, and not only our own, but both, intermingled in the poem, as if the poem were our minds’ common ground.” This individual experience is what Matthew Zapruder discusses in his book Why Poetry: “…when a person falls in love with a poem, it is usually because it feels like a private experience,” a distinct, and specific emotion that can only be achieved through the process of reading the author’s words. This concept, the rendering of the inner world to the outer word, is part of what makes a good poem, a balanced “…between inside and outside, that the membrane has been made impermeable—to write poems means to create impermeability” that “…even the heaviest subjects will be hidden in that lightness; maybe because each individual word is so packed with energy that it contains millions of ways to experience things.”

This impermeability can be hard to achieve. Christensen notes that every writer, whether seasoned or novice, deals with this burden. “Because writing poems, no matter what, is always about being at square one and starting from scratch; every time, about writing the individual poem as if it were the first poem in the world. But only as if it were the first.” It’s an inescapable part of the writing process.

That’s how it is in the beginning: great anxiety and confusion, but also patience with our fear of leaping in, because we know that others have made the leap before us. Deep inside we know that the beginning is a bridge already built, even though it’s not until we step out into empty space that we can feel the bridge beneath our feet.

But that distress is unfounded; the poem, the essay, the story is just beyond the blank page. The emptiness of the page is not to be feared as “…as an image of the great nothingness.” It is a space “…where everything exists, uncreated.” Everything is “… there; it’s just that the hidden and forgotten and unbounded possibility” can be brought forth with words. When a “…poem begins to take shape, the landscape broadens out, and images begin, on their own, to keep words and phenomena together. Where before there was nothing, now there is something; and along with it something else that continues the process…” These words are “a membrane between inside and outside, a membrane that regulates the osmotic exchange between consciousness and the surrounding world.”

An artist should exist within that world. “A couple of years ago I was living in Knebel, down by Mols. My window had a view of trees, a field, and sky. I carried on long conversations with that view…a conversation that had been carried on for centuries…” and in the city, which can “…invite us to take part in aspects of humanity that we haven’t known about; it can awaken our curiosity, our urge to see what is actually going on. And really, isn’t this an excellent work environment for a writer?” It is in these environments that one can see the interconnectedness of things.

This interconnectedness is not only good for writers and artists but for all people, anyone who tries to “plug away for years, trying to get consciousness and vision to hang together… until the world suddenly inscribes itself in them and the difference between human being and the world vanishes, so the world can write itself by means of human consciousness.” For writers, this connection is more apparent because “[l]anguage can’t be separated from the world without separating the world from itself.”

Language is central to human existence. We measure and distinguish civilizations by their ability to communicate. But for Christensen, this determination transcends academic discussions to signal a primal need. “If we couldn’t sing, play instruments, and dance, if we couldn’t tell stories and describe the world for each other, we would never be able to understand the world, nor would the world ever be able to understand itself through us.” Writing answers the human need to convey our understanding of the world. “All the knowledge we have is, in a certain sense, already gathered in the great works of art,” and it is fundamental for humans to want to convey that knowledge, that individual, inner experience, to others. “For as human beings, we can’t avoid being part of the artistic process, where source, creation, and effect are inextricably bound together. Here in our necessity.” Art is essential because humans are bound to it.. Expression through art—through language—is a natural function of being alive. “My expressing myself here is no different in principle from a tree growing leaves. Self-producing, self-regulating biological systems are basically the same, whether they’re called trees or humans.”

This vital human communication connects the writer to the reader through language.

Silk is a noun. All nouns are very lonely. They’re like crystals, each enclosing its own little piece of our knowledge about the world. But examine them thoroughly, in all their degrees of transparency, and sooner or later they’ll reveal their knowledge. Say the word silk, and it vanishes with the sound, but your senses, your memory and knowledge cast back an echo.

This interaction, this necessary communication takes place through small elements of language; nouns, adjectives, verbs, prepositions, and adverbs. Fractions of languages that contain multitudes in their singular and combined forms that connect us to one another, “…it’s exactly that concentration on words and combinations of words, which, in themselves, are essentially empty, that can elicit key memories. Memories that will make it possible for readers to access their own memories.”

Those multitudes lie in the associations with words that all of us carry: the images, the smells, the memories, the symbolic meanings we have learned.

I can say “rose,” and if I close my eyes, a rose will appear before my inner eye, maybe not entirely as visible as it would be in a garden, but visible, and if I open my eyes again and say “rose,” as I’m doing while I prepare this talk, one rose after another will appear, a whole world of roses, in my memory: the first rose that a boyfriend ever gave me, the bouquet of roses when my son was born, rose gardens here and there in the world, the great rose window in Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, and the rose catalog I used when I was writing my novel Azorno, all those rose names: “Rosa hugonis, Rosa pimpinellifolia, Blaze Superior, Virgo and Rosa rugosa, Rosa rubiginosa, Rosa ‘Nevada.’”

As Christensen points out, a rose is not just a rose. It is every rose we have ever seen, touched, and smelled. It is every depiction of a rose we have encountered and everything that has ever been associated with it. The word “rose” contains a vastness that we are all bonded to.

Christensen’s observations on writing and its nature are illuminating, but those essays only comprise half of the collection. The collection opens with personal essays depicting Christensen’s childhood and coming of age. “Freedom, Equality, and Fraternity in the Summer Cottage” and “Interplay” are exemplary in their execution of the form but contain a tone that is not reflected in any other essays. It is a jarring transition for the reader to come to know the author through intimate conversation only to transition to distant metaphysical topics. The Condition of Secrecy is a collection of translated essays that span thirty years, from 1964 -1994, and feels as disparate as those three decades do. Christensen is a talented writer and able to draw connections that few others can see, but that tendency can lead her essays and her collection to feel as though there is no center due to the wide range of subjects, styles, and tones. The experience of reading the collection is best captured in the microcosm of reading Christensen’s “The Regulating Effect of Chance,” the longest of the essays. Christensen begins “The Regulating Effect of Chance” by examining the idea of chance in human existence and from there covers weather modeling, the Roman goddess Fortuna, and then a minute examination of the writing process questioning how exactly our words—as if by magic (or chance)—appear on the page. It is an interesting analysis. How chance exists in things big and small, like weather and writing. How humans have always tried to predict outcomes and know what is unknowable, from the Roman Empire to today. However, the essay does not end there. It leaps into a discussion of paradise and diaspora, Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting, “the German town of Edenkoben,” fragmentary thinking, imagination, and “the grotesqueness of a purely man-made world becomes evident in these fantasy images from The Painted Room, a novel I wrote in the 1970s about the artist Andrea Mantegna, who lived in Mantua in the late 1400s,” among other concepts. The connections are tenuous at times: “I have an anagram that might be useful here. If we take the Italian word for paradise—paradiso—and rearrange the letters, we get diaspora. Diaspora is the Greek word for ‘scattering’ or ‘diffusion.’”

Christensen is not unaware that her analysis has gone far afield. It feels as though she is admitting that “The Regulating Effect of Chance” and its fourteen subsections are a literary junk drawer when in the subsection “Fragments and Roundabout Routes” Christensen observes that Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting also has a section within it that

… appears to include everything that wouldn’t quite fit in with the more practical advice in the other chapters, which consist primarily of detailed instructions for painting monsters, storms, night scenes, trees and smaller plants, morning sunlight, late afternoon sunlight, etc. etc. The various notes that couldn’t be included with those practical instructions are largely theoretical artistic considerations concerning artists’ relationship to their material as a whole, and the issue of beginning any specific work of art.

This is an apt description for not only “The Regulating Effect of Chance,” but for the entire collection.

Despite its disjointed nature, the collection is vital to reiterate the point of language—the point of writing, the point of poetry—is to emphasize the enmeshed nature of humanity: with itself and with the world. “In the human world, first and foremost, in language and mathematics as they’re interwoven within us.”

But our job as writers, as humans is to continue to express and to be expressed. In both regards, it is an active role. “I am and will remain the naive reader, a native inhabitant, an insider who can never see her world from the outside. And my poem will relate to the universe in the same way the eye relates to its own retina. But still, it sees. And it keeps reading.” Our job is to continue to try to achieve balance, that permeability. To see the world from both the inside and outside, to assemble and express our knowledge of the world even in our limited experience of its vastness.

Maybe it shows that in actuality, the world can both read and be read. That impressions can be harvested just as grapes can. That signs can be gathered just as nourishment can. That we as humans can read a multitude of signs, from the motions of the stars and the clouds, through the migrations of birds and shoals of fish, to the language of ants and of the swirling of water at home in the kitchen sink. Everything from astronomy and invisible chemistry to biology and its climates. But ants too read. Trees too read and know within seconds when they should let their leaves droop, if their blossoming is endangered.

Language may be fundamental to civilization, but writing is vital to the individual human experience. “The same millions of ways to experience things can be used when we write a poem. Everything is contained in everything.”

AM Larks writes fiction and nonfiction. She has performed her stories at Lit Up at Town Hall Theatre in Lafayette, California. She is the former Blog Editor of The Coachella Review and contributes reviews and interviews to, and is a reader for, TCR. She has earned a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, a Juris Doctorate, and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts from the University of California Riverside–Palm Desert’s low-residency program. She lives in Northern California.