By eli ryder

By eli ryder

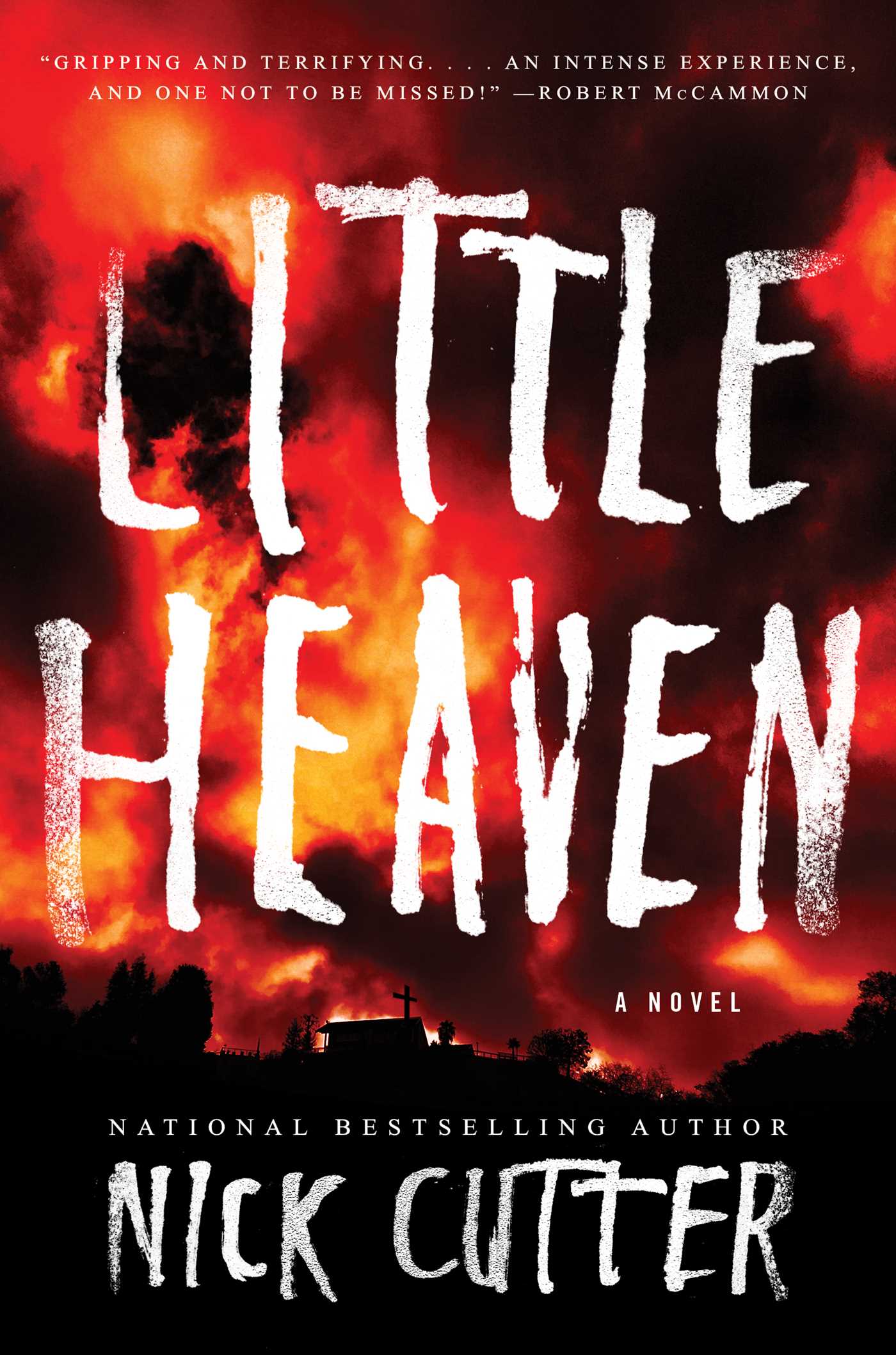

New Mexico, 1965. Three seasoned killers converge on each other, then on a cult leader and a consuming force of darkness that threatens to overtake the world. Fresh, unflinching horror ensues. This is Nick Cutter’s Little Heaven. New Mexico is the perfect sparse setting for this modern take on classic westerns; outlaws, revenge, a maiden in distress, and a reverend that makes the most unhinged Pentecostal tongue-speaker feel perfectly sane all combine in a series of story beats Louis L’Amour would have found comfortably familiar, if he could stomach the visceral punches Cutter weaves throughout, a la Cormac McCarthy. Little Heaven’s New Mexico has “scratch-ass” towns with “straggle-ass” streets in which hired guns ask their targets, “Are you square with your creator?” before dispatching them to what lies beyond.

The story opens with Micah Shughrue’s daughter, Petty, being kidnapped by the right-hand minion of a monster that has risen out of Micah’s past. To save her, Micah must reassemble his old crew and face that monster once again. For each of them, Micah, Minnie, and The Englishman, the task dredges up memories of the last time they were all together, twenty-odd years prior—in Little Heaven. Run by Reverend Amos Flesher, Little Heaven was a cult-like religious compound that provided its members a source of faith until Micah and his crew arrived in search of a missing boy and found far more than they were looking for.

Cutter’s prose is punctuated by staccato sentence structures, which make for quick, gritty pacing that never trips up momentum. The writing weaves back and forth through multiple characters’ points-of-view, making the novel a much faster read than its nearly five hundred pages would otherwise indicate. By spending time in the point of view of almost every character that makes even a minor story-influencing choice, Cutter not only expands the world in which the story takes place, but also the depth of even tertiary characters that likely would have blown by without notice. Virgil, the hapless follower introduced late in the novel, is a prime example. Though just a tertiary character, the close third-person perspective through which we meet him generates a delightfully uncomfortable empathy for a character who simply doesn’t know any better than to do whatever horrible thing he’s told to do. “Virgil was dumb. He was just smart enough to know it. Which was a pretty sad place to pin the tail on that particular donkey.” Aww. Poor Virgil. Without these close-third sections, characters like Virgil would just be background cogs in the gears of plot, and we would miss out on the moments in which we root for or defend them even as they wreak nefarious havoc.

If the bones of this novel hearken back to gunslingers in sage and juniper, then its flesh and blood and skin are rooted in the frightening traditions of monsters in the dark and the powerlessness of humanity against unimaginable evil. Little Heaven wears the markers of its pedigree openly and proudly. There’s no denying a nod to Lovecraft in the unfathomable creatures and the master they serve here; despite seeing the monsters in full view, characters invariably still cannot comprehend what it is they’re seeing because they’re trying to understand the creatures as a part of the natural order to which we all belong. An order these creatures are above and beyond.

Cutter also seems to be paying homage to Stephen King’s body of work. There are obvious similarities to the Gunslinger series in Cutter’s protagonists being, well, three gunslingers, but Cutter also employs the kind of other/under-worldliness that drives all of King’s narratives. In particular, though, IT resonates throughout Little Heaven. The monsters at work here recall Pennywise’s ancient brand of evil and ravenous taste for children, and the human perpetrators of evil are driven by the underworld rot that has taken over the woods. And, of course, there’s the spider.

This is a novel by a horror fan for horror fans, and should earn a look from anyone in search of weirder western stuff, too. Despite the obvious ancestry of this novel, Cutter rewards readers with a fresh experience that departs from its forebears in the most important way: where Lovecraft played in the mind, Cutter starts there and then flays the body. Where King revels in humanity, Cutter opens wounds, salts them, and then gleefully revels in the painful mess he’s made—and only then drives emotional stakes home. Cutter actively seeks out boundaries for the sole purpose of kicking them down to watch us squirm at what’s behind those walls. Little Heaven is uninhibited, unafraid, and a must read.

Eli Ryder writes fiction and drama, teaches literature and composition, and abhors maple bars that dare to parade around without bacon. He is the Drama Editor of The Coachella Review.